Identification of clinical isolates and biofilm formation

Biofilm formation is a microbial survival strategy, and these surface-associated microbial cells facilitate the adherence of microorganisms to living and inanimate surfaces. In the human host, biofilms can serve as a reservoir for spreading new infections and increasing bacterial resistance to antibiotics. Among the E. coli isolates collected in this study, 28.6%, 32.9%, 24.3%, and 14.3% had strong, moderate, weak, and no biofilm formers, respectively. These data were in agreement with those of another study of biofilm formation by uropathogenic E. coli, which showed 23.6% highly positive, 26.3% moderately positive, and 50% weakly positive biofilm formation in the 100 tested strains [42]. The virulence of these uropathogenic E. coli fimbrial adhesins was reported to be triggered by Ag43, which might be the major contributing factor to long-term persistence after the establishment of an initial infection, and the Ag43a gene was responsible for a strong aggregation phenotype that promoted significant biofilm growth [43].

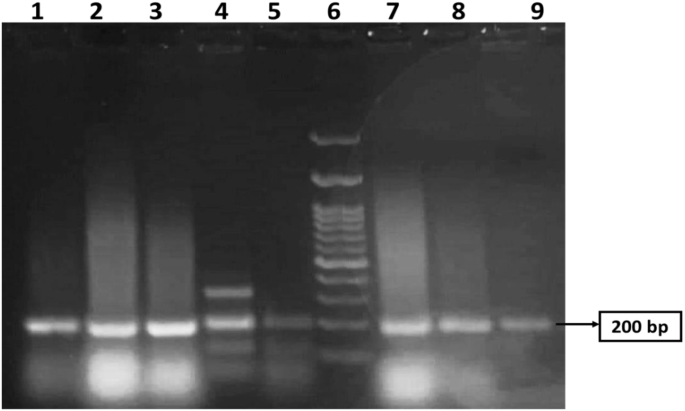

Figure 1 shows the 200 bp PCR-amplified csgA gene in E. coli, which was visualized via gel electrophoresis analysis. The samples were loaded in lanes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, and 9, while lane 6 was loaded with a 200 bp DNA ladder. All the isolates were positive for the csgA gene. An image-editing tool (www.irfanview.net) was used to enhance the representation of the image (original image, supplementary file).

GC‒MS analysis of rosemary oil

Phytochemical constituents identified in dried leaf extracts of Rosmarinus officinalis L. by GC‒MS analysis showed that high concentrations in the extracted rosemary oil were 3,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid (96.56%), eucalyptol (25.68%), and bicyclo[3.3.0]oct-2-en-6-one, 3-methyl (17.84%) (Table 2). This finding suggests that rosemary oil contains a significant amount of oxygenated compounds and phenylpropanoids, which are known for their potential therapeutic properties. Oxygenated compounds and phenylpropanoids have been reported to exhibit various biological activities, such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory effects [44]. GC-MS chromatogram of rosemary oil is available in supplementary file.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

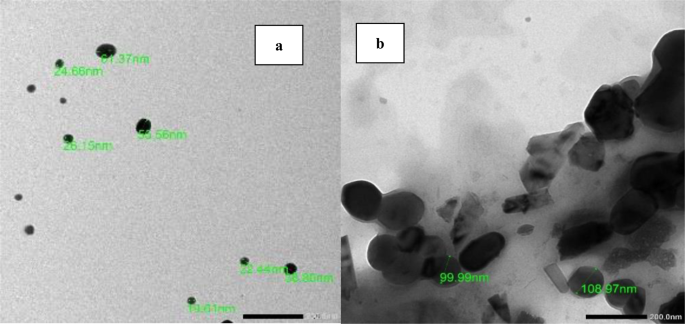

Figure 2 shows TEM images of freshly prepared (a) 0.5% CS nanophytosomes and (b) NSLC nanophytosomes. The CS nanophytosomes had a well-defined spherical shape with an average size of approximately 26 nm and were evenly distributed without any agglomeration. In contrast, the NSLC nanophytosomes were larger and less uniform in shape. The particle size and shape results of the nanoparticles are consistent with the findings of our previous work [45].

Particle size (PS), zeta potential (ZP), polydispersity index (PDI), and entrapment efficiency (EE%)

Table 3 shows that the NSLC nanophytosomes had a significantly greater PS (176.70 ± 12.30 nm) than did the 0.5% CS and 1% CS nanophytosomes, which had PSs of 22.54 ± 2.92 nm and 34.59 ± 4.00 nm, respectively (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.001). This difference may be due to the composition of NSLC nanophytosomes, which includes a mixture of solid and liquid lipids. In contrast, the CS nanophytosomes are primarily composed of CS. The PS significantly increased when the CS concentration was increased from 0.5 to 1% (t-test, p < 0.001).

The surface charge of nanoparticles in colloids can be used to predict their long-term stability. The NSLC nanophytosomes exhibited a negative ZP of -32.71 ± 2.07 mV, while the 0.5% CS nanophytosomes had a positive ZP of 11.5 ± 0.05 mV due to the unbranched cationic nature of the CS. The stronger surface charges of NSLC nanophytosomes suggest that they may be more stable, as the nanoparticles can repel each other more effectively. In contrast, the weaker surface charges around the CS nanophytosomes may not be sufficient to prevent aggregation over time, suggesting the necessity of lyophilization for long-term storage stability.

Compared with 0.5% CS nanophytosomes, the NSLC nanophytosomes had significantly lower PDI values (0.45 ± 0.01 and 0.57 ± 0.14, respectively) (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.001). This means that the NSLC nanophytosomes were more monodisperse than the CS nanophytosomes were. Moreover, increasing the CS concentration resulted in a more heterogeneous mixture, as indicated by a significant increase in the PDI (t-test, p < 0.05). In addition, both the NSLC and CS nanophytosomes exhibited high entrapment efficiencies of 93.47 ± 0.90% and 93.12 ± 1.05%, respectively. However, due to the potential benefits of smaller particle sizes in increasing drug loading, 0.5% CS nanophytosomes were selected for further investigation.

Lyophilization of nanoparticles

Freeze-drying is a technique that converts colloidal dispersions into dry powders with enhanced long-term storage stability. The process involves freezing the nanoformulation, reducing the pressure, and removing water by sublimation and desorption under vacuum. However, freeze-drying process poses the challenge of maintaining the original formulation structure, as ice nucleation during the process can alter the formulation morphology, cause physical collapse, and induce colloidal instability and nanoparticle aggregation [46]. To overcome these problems, a cryoprotectant, such as mannitol, can be used to immobilize nanoparticles in an amorphous matrix by replacing water molecules and preventing sample collapse due to osmotic pressure and stress. The lyophilization process has yielded soft, loose flake appearance, free-flowing CS nanophytosomes powder with short resuspension time. The reduced moisture content through lyophilization enhances stability and ensures a longer shelf life by preventing microbial growth and chemical degradation. Upon reconstitution, the lyophilized powder quickly disperses, forming a homogenous solution, which is crucial for efficient drug delivery and patient compliance.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and biofilm inhibition

Table 4 presents the results of MIC testing of CS and NSLC nanophytosomes against E. coli compared to those of rosemary oil. The data showed that both types of nanophytosomes had significantly lower MICs against E. coli than rosemary oil alone, with a reduction rate of 45.8% for NSLC nanophytosomes and 87.5% for 0.5% CS nanophytosomes. Further Mann‒Whitney tests confirmed that the MIC was significant lower for CS phytosomes than for NSLC phytosomes (p < 0.01), which may be attributed to the synergistic effect of CS and rosemary oil when combined in nanophytosomes. Consequently, CS nanophytosomes were selected for biofilm inhibition testing.

The outer membrane of E. coli has a unique structure that acts as a selective barrier, combining a highly hydrophobic lipid bilayer and pore-forming proteins with specific size exclusion properties. Therefore, nanopartilces can enter the outer membrane through either a lipid-mediated route or general diffusion porins for hydrophilic entry [47]. The small particles of CS nanophytosomes are able to utilize the porin-mediated permeability pathway to gain access to the cells of E. coli and interact with the water-soluble proteins and nucleic acids within the bacterial cell, resulting in a significantly reduced MIC against E. coli. In contrast, larger particles of NSLC nanophytosomes have to diffuse across the lipid bilayer of the outer membrane, a more challenging and rate-limiting process that contributes to the observed variation in the antimicrobial efficacy between the two types of nanophytosomes.

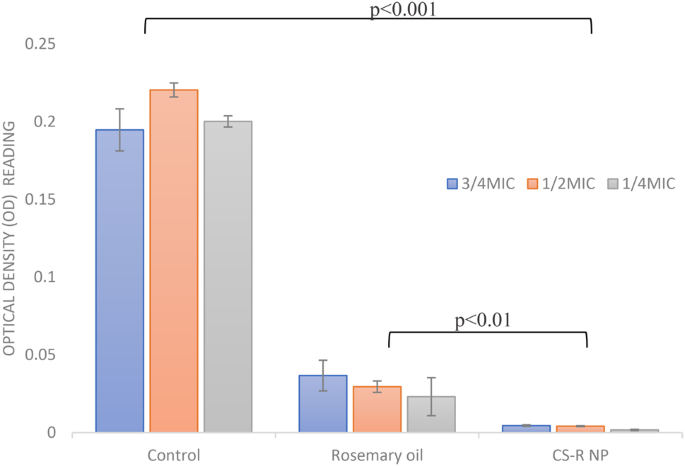

To evaluate the efficacy of sub-MICs of rosemary oil and 0.5% CS phytosomes at ¾ MIC, ½ MIC, and ¼ MIC in inhibiting the formation of strong biofilms produced by E. coli, a crystal violet staining assay was used. Compared with the control, the CS nanophytosomes significantly inhibited biofilm formation at all concentrations (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.001), as shown in Fig. 3. Compared with those of rosemary oil, the biofilm formation of the CS nanophytosomes also substantially decreased at all concentrations (p < 0.01). The significant differences observed between ¼ MIC and ½ MIC, as well as between ¼ MIC and ¾ MIC (p < 0.001), of the CS nanophytosomes suggested that lower sub-MIC concentrations of CS phytosomes may be more effective at inhibiting biofilms produced by MDR E. coli. However, no significant difference was found between the ½ MIC and ¾ MIC (p > 0.05), indicating that increasing the concentration of CS nanophytosomes beyond a certain point may not provide any additional benefits in terms of biofilm inhibition. Overall, these results suggest that the use of sub-MIC concentrations of CS nanophytosomes could be a promising strategy for preventing the formation of strong biofilms by MDR E. coli. Furthermore, the addition of chitosan into nanophytosomes enhances its ability to penetrate the biofilm matrix more effectively through electrostatic interactions between positively charged chitosan molecules and negatively charged biofilm constituents which contain extracellular polysaccharides, proteins, and DNA [48]. On the other hand, rosemary oil contains bioactive metabolites with antimicrobial properties that could interact with bacterial cell membranes, disrupt genetic material and nutrient transport leading to compromised bacterial cell functionality and structural integrity [49]. Therefore, incorporating rosemary oil into nanoformulation may augment synergistic antimicrobial efficacy.

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy

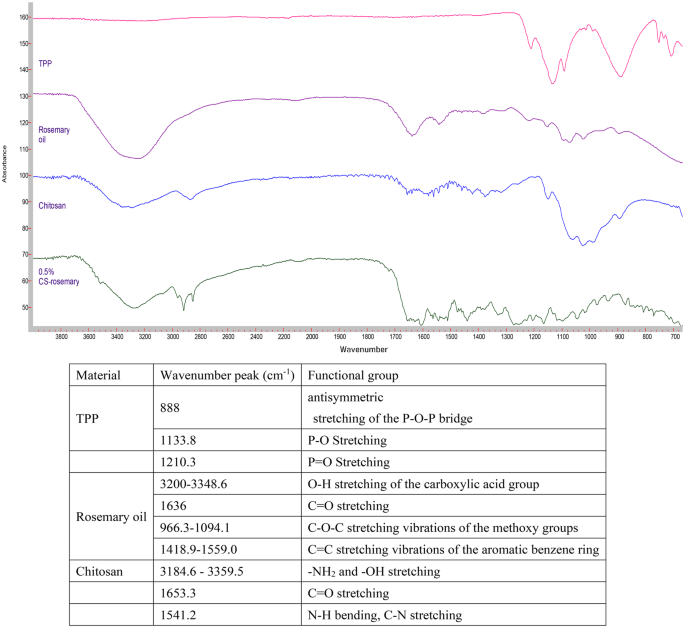

The FTIR spectra of TPP, rosemary oil, CS, and 0.5% CS nanophytosomes are presented in Fig. 4. The phosphate groups in the TPP molecule exhibit peaks at 888 cm− 1, 1133.8 cm− 1, 707.3 cm− 1, 752.4 cm− 1, and 1210.3 cm− 1 due to their different vibrational modes [50]. The FTIR spectrum of the extracted rosemary oil showed the characteristic absorption peaks of 3,5-Dimethoxybenzoic acid which was the major component of the extracted rosemary oil. It is an aromatic carboxylic acid with two methoxy (OCH3) substituents at the 3 and 5 positions of the benzene ring [51]. A broad absorption band observed at around 3200–3348.6 cm− 1 corresponding to the O-H stretching vibration of the carboxylic acid group. A strong absorption peak at 1636 cm− 1 corresponding to carbonyl double bond (C = O) stretching. Many absorption peaks appeared around 966.3–1094.1 cm− 1 were related to the C-O-C stretching vibrations of the methoxy groups. There were also multiple absorption bands in between 1418.9 and 1559.0 cm− 1 corresponding to the C = C stretching vibrations of the aromatic benzene ring. Our FTIR study result was similar to the published literature on rosemary oil [52]. FTIR absorption peaks in rosemary oil is available in the supplementary files.

On the other hand, the spectrum of pure chitosan exhibited the characteristic broadband with peaks around 3184.6–3359.5 cm− 1 due to amino (-NH2) and hydroxyl (-OH) stretching. A weak band with a peak at 1653.3 cm− 1 corresponds to the C = O stretching vibration and a strong band at 1541.2 cm− 1 indicates the presence of an amide bond with the N-H bending vibration and C-N stretching vibration of the amide groups [53]. Comparing the FTIR spectrum of the pure chitosan and CS-nanophytosomes, we identified slightly changes in the absorption bands, their positions, intensities, and shapes which can provide insights into the nature and extent of the ionic interactions occurring in the CS-nanophytosomes. These changes were demonstrated by the shifts in several characteristic absorption bands in the FTIR spectrum. The shape of the absorption bands of CS-nanophytosomes were becoming broader and more complex compared to the pure chitosan due to the presence of multiple overlapping vibrations. In addition, a new absorption band appeared at 1517.7 cm− 1 indicated the formation of ionic interactions between the amino group of chitosan and the carboxylate group of rosemary oil, corresponding to the asymmetric stretching of the carboxylate group.

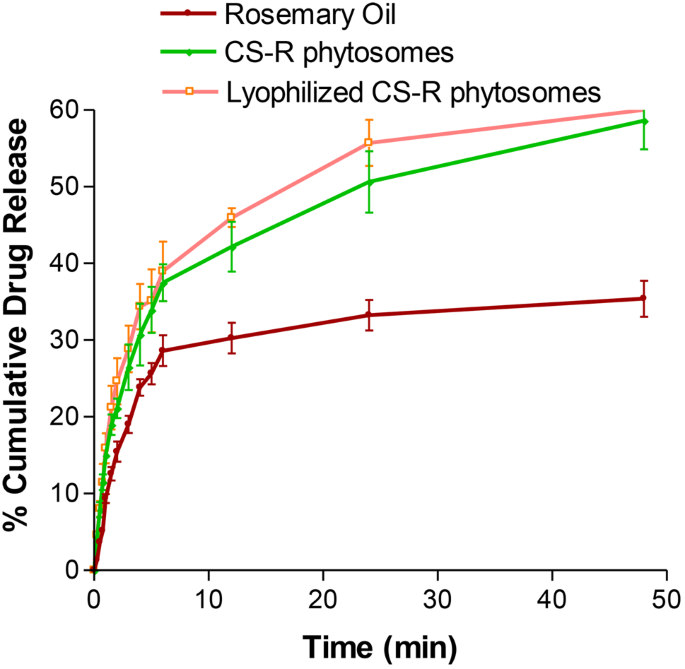

In vitro drug release

The release of rosemary oil, CS nanophytosomes, and lyophilized CS nanophytosomes over a 48-h period is shown in Fig. 5. Pure rosemary oil had a significantly lower percentage of 35.4 ± 2.36% release over 48 h, while the CS nanophytosomes and lyophilized CS nanophytosomes had markedly greater percentages of 58.6 ± 3.69% and 56.9 ± 5.01%, respectively (p < 0.001). This can be attributed to the hydrophilic nature of the nanophytosomes because the oil is trapped in the chitosan nanoparticles; therefore, an increase in the release of rosemary oil from the nanophytosomes occurs when they are in contact with water. Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference between the drug release of the unlyophilized and reconstituted lyophilized CS nanophytosomes (t-test, p > 0.05). These results suggest that the freeze-drying process did not adversely affect drug release or induce any significant changes in the nanophytosomes.

Worth noting that the drug release profiles of all the tested samples showed an initial rapid release within the first 6 h, followed by a more sustained release. This initial burst release of the drug could promptly increase the desired plasma concentration in a short time, which is crucial for effectively combating infections. Moreover, the subsequent sustained release after 6 h might provide additional benefits by maintaining the dose for a longer time, thereby reducing the potential for side effects. These findings also highlight the potential of CS nanophytosomes as a promising drug delivery system.

The drug release kinetics of the CS nanophytosomes were analyzed using five mathematical models: zero order, first order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer–Peppas, and Hixson–Crowell [54]. The model with the highest correlation coefficient (R2) was considered the best-fitting model. The result showed that the overall drug release of the CS nanophytosomes over 48 h was best fitted by the first-order kinetic model, with an R2 of 0. 0.9807, indicating that the rate of drug release is directly proportional to the amount of drug remaining in the formulation. However, the drug release exhibited two patterns, with an initial fast release followed by a later steady release. Therefore, the kinetic models were reapplied to these two patterns separately. For both the initial rapid release within 6 h and the subsequent slow release after up to 48 h, the Higuchi model was the best fit, with R2 values of 0.9915 and 0.9938, respectively. This suggest that drug release from CS nanophytosomes is strongly influenced by diffusion through the chitosan hydrogel matrix in the nanoformulation.

Physical stability study

The effects of lyophilization on the stability of the CS nanophytosomes were evaluated by measuring the PS, ZP, and PDI for 3 months at room temperature (Table 5). The data showed that there was no significant difference in the PS, ZP, or PDI between unlyophilized and lyophilized CS nanophytosomes (p > 0.05). However, upon storage, both samples exhibited significant changes in the PS and ZP (p < 0.001). The PS increased from 22.54 ± 2.92 nm to 339.33 ± 23.16 nm for unlyophilized CS nanophytosomes and from 45.66 ± 3.26 nm to 352 ± 30.25 nm for lyophilized CS-R nanophytosomes in three months. Although there were no visible physical changes in any of the samples stored for 3 months, it is expected that reorganization of inter/intramolecular hydrogen bonding and additional intermolecular entanglement of the CS particles might have occurred during long-term storage, leading to particle agglomeration. Additionally, the residual moisture in the freeze-dried samples could also affect the PS of the CS nanophytosomes. The ZP of the lyophilized CS nanophytosomes was reduced from a fresh sample of 12.36 ± 0.14 to 6.03 ± 0.05 mV after three months. The presence of more neutral surface charges around the CS nanophytosomes during storage might not be able to prevent aggregation due to the absence of an interparticle repulsive force. Furthermore, a narrowing of the PDI was observed in both unlyophilized and lyophilized CS nanophytosomes after three months, which might be attributed to the presence of more unified larger nanoparticles.

In general, nanoparticles have a high surface-to-volume ratio, which makes them prone to aggregation over time. As the nanoparticles aggregate, the overall surface area-to-volume ratio changes, resulting in the reduction of zeta potential. During storage, ions or other molecules in the formulation may be adsorbed onto the surface of CS nanophytosomes, leading to a change in the zeta potential. The alter in PS and ZP during storage may be also due to other factors such as temperature variations, exposure to light, humidity and water content in the formulation, impacting the efficacy of rosemary nanophytosomes. To maintain a consistent zeta potential, several strategies can be used in the future studies, such as incorporating stabilizing agents in the formulation, use of surface coating technique, and appropriate control the storage conditions, such as temperature, pH, light and ionic strength of the storage medium to optimize the storage stability.

In vivo UTI study

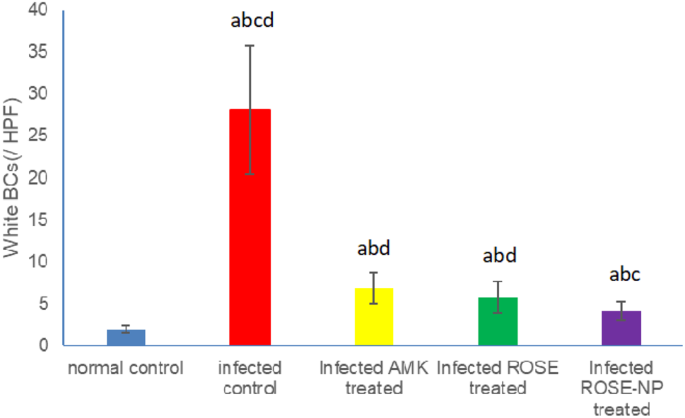

Urine analysis of WBCs

The untreated rats infected with UTI (Group II) exhibited a significant increase in WBC count (28.33 ± 4.12/HPF) compared to healthy rats (2.08 ± 0.81/HPF) (P < 0.001). Upon treatment, infected rats receiving either amikacin (Group III) or pure rosemary oil (Group IV) demonstrated substantial reductions in urine WBC count (6.83 ± 1.29/HPF and 5.83±/HPF, respectively). Interestingly, no statistical difference was observed between the WBC counts in these two treatment groups (p > 0.05), suggesting that rosemary oil has a similar effect in reducing WBC count as amikacin. Notably, the most significant reduction in WBCs occurred in Group V (4.17 ± 0.91/HPF), where rats were treated with CS nanophytosomes, compared to Group II (P < 0.001). The WBC count was significantly reduced by CS nanophytosomes in comparison to either Group III or Group IV (p < 0.05). This finding highlights the enhanced antibacterial effect of rosemary when delivered via CS nanophytosomes (Fig. 6). CS nanophytosomes effectively interacted with cell membranes, disrupting their structure and function, leading to leakage of cellular components [55].

Effect of treatment with amikacin (AMK), rosemary oil (ROSE) and CS- Nanophytosomes on WBC’s count in the urine on infected rats (n = 6). a: significant difference compared to normal control. b: significant difference compared to infected control. c: significant difference compared to infected AMK treated group. d: significant difference compared to infected ROSE treated group (p < 0.001)

Biochemical analysis

We investigated the impact of different treatments on key biochemical markers associated with UTI. Table 6 presents a comprehensive overview of the urea, creatinine, CRP, MDA, TAC, and IL-10 levels across the five groups. Compared to Group I, Group II rats exhibited elevated serum levels of both urea and creatinine, indicating compromised kidney function due to the infection. All treatment cohorts (Groups III-V) showed a significant reduction in creatinine levels compared to Group II (p < 0.001). However, amikacin (Group III), a positive control antibiotic, did not significantly improve urea levels compared to Group II (p > 0.05). Amikacin is known to have nephrotoxic effects, as it remains unmetabolized in the body, leading to its accumulation in the proximal tubule upon excretion in urine, where it generates free radicals causing renal damage [56]. Conversely, rosemary oil, particularly when delivered via CS nanophytosomes (Group V), normalized the serum concentrations of both urea and creatinine, underscoring its significant nephroprotective attributes. This observation aligns with the findings reported by Abdel-Azeem AS et al. [57], suggesting that rosemary oil may modulate intracellular pathways associated with DNA repair to ameliorate glomerular function and mitigate renal injury. Furthermore, rosemary oil has demonstrated the ability to activate the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, thereby upregulating the expression of various protective genes and bolstering the efficacy of the endogenous cellular antioxidant defense system [58]. Moreover, the administration of CS nanophytosomes further enhanced the restoration of kidney function to baseline levels subsequent to UTI.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a vital role in various biological processes, including apoptosis, immunity, and defense mechanisms against pathogens. However, elevated ROS levels can lead to cellular damage and oxidative stress (OS). Antioxidants sourced from endogenous or exogenous origins can act as protective shields and mitigate the detrimental impacts of OS [59]. Moreover, there exists a connection between oxidative stress (OS) and inflammation. These two processes are closely linked, often influencing each other. The connection between OS and inflammation involves a positive feedback loop: inflammation generates ROS, which, in turn, exacerbate inflammation. In general, OS can be evaluated by testing MDA levels, the primary marker of lipid peroxidation caused by ROS, and TAC levels which reflects the body’s ability to counteract ROS [60].

Infection led to an increase in serum MDA and a decrease in TAC levels were observed in Group II rats, indicating OS. In contrary, all treatment groups (Groups III-V) exhibited a significant decrease in MDA levels and an increase in TAC levels compared to Group II (p < 0.001), with Group V showing the most pronounced improvement, where TAC levels approached almost normal levels compared to Group I (p > 0.05). Amikacin and rosemary oil effectively alleviated OS through their antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. Rosemary oil, in particular, demonstrated a more potent antioxidant effect than Amikacin, further enhanced when delivered via CS nanophytosomes. Rosemary oil contains active phytochemicals such as flavonoids, polyphenols, and diterpenes, with strong antioxidant properties. These phytochemicals exhibite antioxidant capabilities by electron donation to reactive radicals, thereby reducing their reactivity, enhancing stability, and minimizing interactions with vital biomolecules such as DNA, lipoproteins, and polyunsaturated fatty acids [61].

Furthermore, the elevation of CRP and IL-10 levels are used to assess the progression of inflammation. UTI often results in inflammation as a response to bacterial invasion, leading to inflammation. When bacteria infiltrate the body, macrophages release cytokines like IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. These cytokines initiate a series of inflammatory cascade through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. Although this response aims to eliminate the infection, it can also result in substantial harm to the host tissue [62].

CRP is an acute-phase inflammatory protein that becomes elevated during various inflammatory conditions, including cardiovascular diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, and infections [63]. On the other hand, IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine which plays a crucial role in regulating inflammation during UTIs. In this study, untreated UTI rats (Group II) showed a significant increase in CRP levels and a decrease in IL-10 levels compared to those in normal control rats (Group I) (p < 0.001). In contrast, all treatment groups (Groups III-V) demonstrated a significant decrease in CRP levels and an increase in IL-10 levels, with Group V treated with CS nanophytosomes exhibiting the most remarkable improvement compared to the untreated rats in Group II (p < 0.001).

The antibacterial effect of both amikacin and rosemary oil leads to alleviation of inflammation, however, rosemary oil has additional anti-inflammatory mechanisms that have been documented [64]. It exerts anti-inflammatory activity through the reduction of the transcription factor NK-κB, hindering the pro-inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, synthesis and inhibiting synthesis of COX-2 enzyme, leading to decrease of arachidonic acid-metabolites downstream production [65]. The ability of rosemary oil to neutralize the reactive species generated during inflammation by its anti-oxidant properties may also mitigate damage caused by inflammation [66]. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory effect was enhanced when rosemary oil was delivered via nanophytosomes due to improved bioavailability.

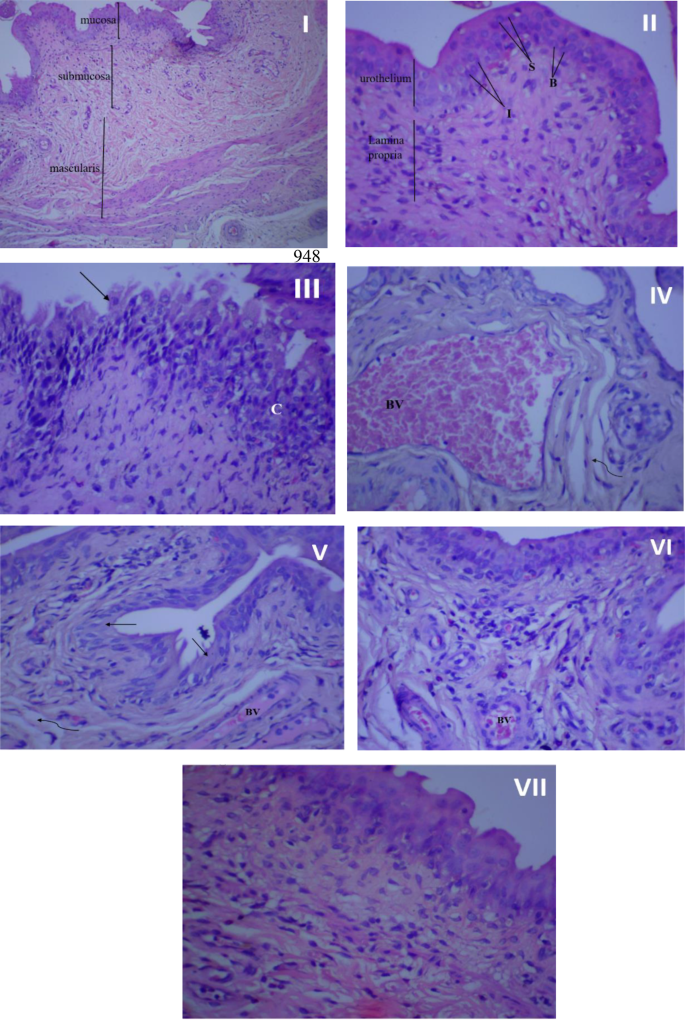

Histopathological examination

Figure 7 illustrates the histopathological findings of the rat urothelial mucosa. The bladder tissue of rats in the control groups (I, II) appeared normal, devoid of hyperplasia or inflammatory cells. However, following infection, the bladder tissues suffered significant damage, characterized by necrosis, urothelium desquamation, inflammatory cell infiltration, fibrosis, and congested blood vessels (III, IV). Treatment with amikacin (V), rosemary oil (VI), or CS-R nanophytosomes (VII) mitigated these pathological changes. Among these treatments, the CS-R nanophytosome-treated rats exhibited the most remarkable improvement, displaying a significantly enhanced and well-defined urinary bladder architecture.

Histopathological examination of rat’s urothelial mucosa. (I) Normal bladder tissue (no infection and no treatment), x100 magnification. (II) Normal bladder tissue, x 400 magnification. (III) Bladder urothelium in the infected control group with chronic inflammation (C) in lamina propria, and urothelium desquamation (↑), x 400 magnification. (IV) Bladder urothelium in the infected control group showing dilated, congested blood vessel (BV), and mild fibrosis (wavy arrow). (V) Urinary bladder of rat treated with amikacin showing moderate inflammation in lamina propria, desquamation of urothelium (↑), mild fibrosis (wavy arrow) and congested blood vessels (BV), x 400 magnification. (VI) urinary bladder of rosemary oil treated rat showing many inflammatory cells beneath to urothelium, small congested blood vessel (BV) and Intact urothelium, x 400 magnification. (VII) urinary bladder of CS nanophytosomes treated rat showing significant improvement with well-defined urinary bladder architecture and some inflammatory cells in lamina propria, x 400 magnification

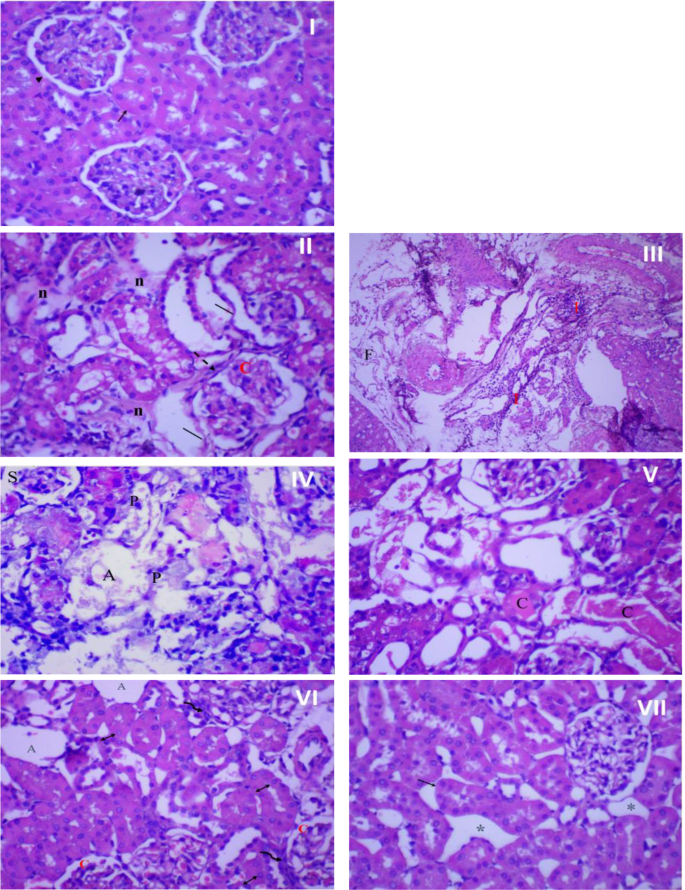

Figure 8 presents the histopathological examination results of rat kidney tissue. In the control group (I), the kidney tissue showed a normal structure with a healthy epithelial lining. However, infection resulted in significant kidney tissue damage characterized by necrosis, architectural loss, and infiltration of inflammatory cells (II), accompanied by fibrosis and congested blood vessels (III). Interestingly, the impact of amikacin treatment on kidney tissue differed from its effect on bladder tissue. In the kidneys, the renal tubules were damaged, shrank, and atrophied, with pyknotic nuclei in most cells (IV, V). However, treatment with rosemary oil (VI) or CS nanophytosomes (VII) alleviated these pathological changes. The most substantial improvement was observed in rats treated with CS nanophytosomes (VII). These rats exhibited a dramatic improvement with well-defined renal tubules showing mild dilatation and spacing between them. The improved architecture of both the kidney and bladder, observed in CS nanophytosomes, supports their antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and nephroprotective effects, as demonstrated in our study.

Histopathological examination of rat’s kidney. (I) Normal kidney tissue (no infection and no treatment) showing normal kidney architecture of proximal tubules (↑) with normal epithelial lining, and glomerulus (►), x 400 magnification. (II) Kidney in the infected control group showing severe damage with loss of kidney architecture, mild necrosis (n), congested glomerulus (C) with thick glomerulus wall (dash arrow), and enlarged, disorganized, desquamated (│) renal tubules, x 400 magnification. (III) Kidney in the infected control group showing severe inflammation (I) and fibrosis (F), x 100 magnification. (IV) Kidney of rat treated with amikacin showing damage and disorganization of kidney tubules, shrank (S), and atrophied (A) glomeruli. Most cells showing pyknotic (P) nuclei, x 400 magnification. (V) kidney of rat treated with amikacin showing severe and widespread necrosis of tubular epithelial cells. Most cells lose its architecture with cast (C) formation, x 400 magnification. (VI) kidney of rosemary oil treated rat showing atrophied (A) and congested (C) glomeruli surrounded by inflammatory cells (wavy arrow) and tubular dilatation with vesiculated nuclei (↕), x 400 magnification. (VII) kidney of CS nanophytosomes treated rat showing dramatic improvement, well-defined renal tubules with mild dilatation (↑) and spacing (*) between tubules, x 400 magnification