Synthesis and characterization of NM-PB Nanozymes

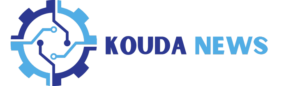

The synthesis of PB nanoparticles is described in detail in method. The morphology and size of PB nanozyme can be clearly observed through the utilization of SEM and TEM techniques (Fig. 1A). The results indicate that the PB nanozyme exhibits a well-defined cubic crystal structure. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns reveal distinct diffraction planes of PB at 17.5° (200), 24.8° (220), 35.4° (400), and 39.7° (420) as shown in Fig. 1B. The chemical state of PB was characterized using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). As depicted in Fig. 1C, the peaks observed at Fe2P3/2 (711.98 eV) and Fe2P1/2 (720.78 eV) correspond to the presence of FeIII in Fe3[Fe2(CN)6]4, while the peak at 707.88 eV indicates the existence of Fe2P3/2 in [Fe2 (CN) 6]4−.

To visualize the membrane fusion, a 1:1 protein weight ratio of Dio-labeled Neutrophil membranes (N) and Dil-labeled macrophage membranes (M) was prepared and sonicated at 37 °C for 10 min. Using the BCA method and inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), the ratio of the cell membrane to PB was calculated. The results showed that the neutrophil-macrophage hybrid membrane accounts for 31.5% of the NM-PB nanozyme, while Prussian blue accounts for 68.5%. CLSM revealed a significant co-localization of the fluorescent signals originating from the NM hybrid membrane (Fig. 1G). Then, the same concentration of PB nanozymes (200 µg/mL) was mixed with an equal volume of cell membranes, and the mixed solution was sonicated in an ice bath for 10 min to form N-PB, M-PB, NM-PB nanozymes by the ultrasonic method. Additionally, Coomassie brilliant blue staining analysis revealed that the protein bands observed on NM-PB were comparable to those of isolated N and M fractions, as indicated by the green and red arrows, thereby indicating the presence of membrane proteins (Fig. 1G). The presence of thin film coatings on the surfaces of NM-PB, N-PB, and M-PB nanozymes was confirmed through direct observations via TEM and SEM. As depicted in Fig. 1D-E, Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis showed that the average particle size of PB is 108.3 nm. However, after modification with cell membranes, the sizes of the nanozymes increased significantly: N-PB to 156.5 nm, M-PB to 154.1 nm, and NM-PB to 159.0 nm. The Zeta potential measurements revealed that NM-PB (-19.0 mV), N-PB (-28.4 mV), and M-PB (-23.7 mV) nanozymes exhibit a significantly higher negative charge compared to the unmodified PB (-17.1 mV). The presence of a strong negative zeta potential on the surface of cell membranes is responsible for this phenomenon, indicating the successful modification of PB nanozymes with cellular membranes.

Characterization of NM-PB nanozymes and targeting capacity of NM-PB nanozymes in vitro. (A) SEM images (scale bar = 200 nm) and TEM images (scale bar = 20 nm) of PB, N-PB, M-PB, NM-PB nanozymes. (B) XRD pattern of PB nanozymes. (C) XPS spectra of PB nanozymes in the Fe 2p region. D–E) DLS and Zeta potential analysis of PB, N-PB, M-PB, and NM-PB PB nanozymes. F) The concentrations of iron measured by ICP-OES in various groups (n = 3). G) CLSM images of the neutrophil-macrophage hybrid membrane (scale bar = 10 μm); SDS-PAGE protein analysis of PB nanozymes, N, M, NM, N-PB nanozymes, M-PB nanozymes, and NM-PB nanozymes by Coomassie blue staining. H) Intracellular uptake of N-PB, M-PB, and NM-PB nanozymes (the blue indicates nucleus stained with DAPI, the red indicates N-PB, M-PB, and NM-PB nanozymes stained with Dil) (scale bar = 20 μm). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparison test

In vitro biocompatibility and targeting capability of NM-PB nanozymes

The non-toxicity of nanomedicine is an essential prerequisite for its successful clinical translation. To assess the biocompatibility of NM-PB nanozymes and investigate its potential anti-inflammatory effects in vitro, we performed cytotoxicity assays utilizing FHC cells and RAW 264.7 immune cells. After exposing FHC cells and RAW 264.7 cells to varying concentrations of NM-PB nanozymes for 24 h, even at high concentrations of PB nanozymes (200 µg/mL), cell viability remained above 90% (Fig. S1A-B). These results confirm that NM-PB nanozymes exhibit excellent biocompatibility, positioning them as viable candidates for drug delivery applications in nanotherapeutics.

To further investigate the targeting capability of NM-PB nanozymes, we established a colitis cell model [32]. The targeting efficacy of NM-PB nanozymes on FHC cells was subsequently evaluated. The cell membrane was labeled with Dil fluorescent dye for CLSM visualization. Cells were incubated with N-PB/Dil, M-PB/Dil, and NM-PB/Dil nanozymes (at an PB concentration of 200 µg/mL) for various durations (2 h, 4 h, 8 h, 12 h, and 24 h). CLSM imaging revealed significantly greater intracellular accumulation of nanoparticles in the NM-PB group compared to the N-PB and M-PB groups (Fig. 1H, Fig. S2A). The iron content in cells was determined using ICP-OES to further validate this finding. Compared to the PB group, N-PB group, and M-PB group, the NM-PB group exhibited the highest iron content in colitis cell models. This further indicates that NM-PB nanozymes enhanced the uptake of PB nanozymes (Fig. 1F). It is evident that nanozymes modified with two types of cell membranes possess dual targeting abilities, which consequently enhances their enrichment and uptake capacity at the lesion site.

Assessment of the ROS scavenging capacity of NM-PB nanozymes in vitro

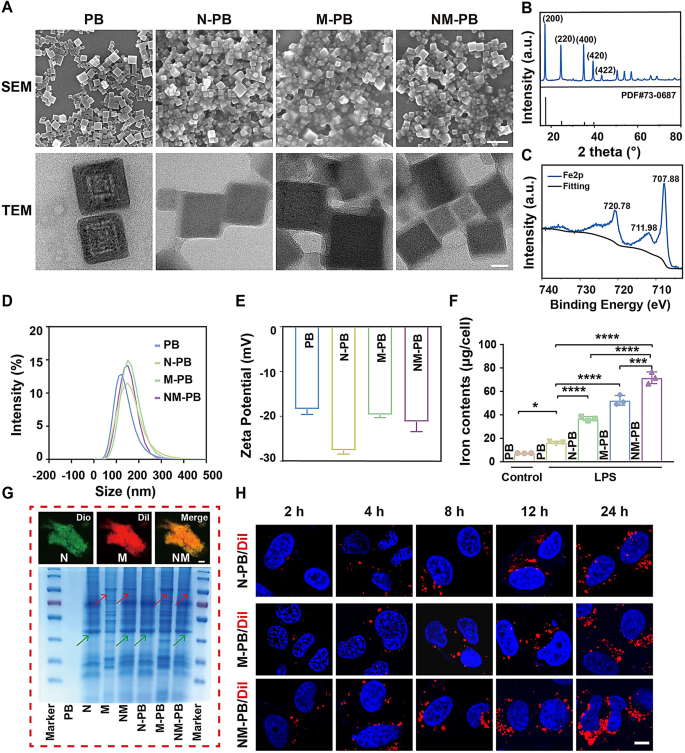

The Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) technique is extensively utilized for the precise detection of free radicals due to its exceptional sensitivity [34]. Consequently, the measurement of inflammation-related species such as •OH, •OOH, and H2O2 following NM-PB nanozymes administration was further conducted using ESR. The ESR results demonstrated a significant reduction in the characteristic peak intensities of BMPO /•OH, BMPO/•OOH and TEMPO/ H2O2 with the application of NM-PB nanozymes (Fig. 2A-C).

The excessive production of ROS in cells, induced by a state of total oxidative stress, triggers a cascade of protein kinases in inflammatory tissues, thereby promoting oxidative damage [10]. The potent antioxidant properties of NM-PB nanozymes prompted us to investigate the potential of NM-PB nanozymes in restoring cell survival under conditions of high oxidative stress, as well as assessing the in vitro capacity of NM-PB nanozymes to eliminate ROS. The LPS group is a colitis cell model established by LPS-induced FHC cells, followed by treatment with PB, N-PB, M-PB, and NM-PB nanozymes at equivalent doses, respectively. Subsequently, DCFH-DA staining was employed to assess ROS levels. As depicted in Fig. 2E and Fig. S2B, a significant increase in green fluorescence signal was observed in FHC cells within the LPS group. Notably, treatment with PB, N-PB, M-PB, and NM-PB nanozymes resulted in reduced ROS levels compared to the LPS group, with NM-PB nanozymes exhibiting the most pronounced ROS scavenging capability among all tested formulations. We further conducted quantitative analysis of intracellular levels of ROS using flow cytometry, which is consistent with the previous results (Fig. 2D). These findings indicate that PB nanozymes, possessing antioxidant enzyme activity, effectively eliminates ROS and protects cells from oxidative stress. Importantly, the antioxidant effect was particularly pronounced in the NM-PB group, suggesting that the dual targeting ability of neutrophil-macrophage hybrid membrane enhances cellular uptake of PB nanozymes and thereby augments its antioxidant efficacy.

The colonic epithelial cells in UC lesions are subjected to damage caused by ROS, leading to the subsequent release of a significant amount of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) into the intercellular space. These DAMPs stimulate the differentiation of macrophages into a pro-inflammatory phenotype known as M1 macrophages, which secrete various pro-inflammatory cytokines. These cytokines can further enhance intracellular ROS production, thereby establishing a detrimental cycle of inflammation and oxidative stress [35, 36].

The anti-inflammatory efficacy of NM-PB was confirmed by measuring cytokines associated with inflammation using RT-qPCR. As depicted in Fig. 2F, the mRNA expression levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 exhibited a significant decrease following treatment with PB, N-PB, M-PB, and NM-PB nanozymes when compared to the LPS group. Notably, NM-PB nanozymes demonstrated a particularly pronounced anti-inflammatory effect. Furthermore, cellular immunofluorescence analysis revealed consistent findings regarding the changes in TNF-α inflammatory factor within the colitis cell model. Remarkably reduced expression of TNF-α was observed after NM-PB nanozymes treatment (Fig. 2G, Fig. S2C). These results collectively indicate that NM-PB nanozymes possesses potent anti-inflammatory capabilities.

The apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells in UC can be attributed to the secondary damage inflicted on intestinal cells by ROS [37]. The anti-apoptotic capability of NM-PB nanozymes was confirmed by evaluating apoptosis-related biomarkers via Western Blot (WB). The expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax was significantly suppressed in the N-PB, M-PB, and NM-PB groups compared to the LPS group, as shown in Fig. 2J and Fig. S2D. Conversely, an upregulation in the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2 was observed (Fig. 2J, Fig. S2E). Notably, among these groups, the NM-PB group exhibited superior anti-apoptotic capability. Therefore, it can be inferred that NM-PB nanozymes effectively mitigates ROS-induced cell apoptosis.

Based on the close correlation between intestinal barrier dysfunction and the pathogenesis of UC [38]. The tight junction and adherens junction proteins, including ZO-1, occludin and E-cadherin [39]. We hypothesize NM-PB nanozymes can restore the impaired intestinal barrier function in the LPS-induced cellular colitis model. Subsequently, various treatments including PB, N-PB, M-PB, and NM-PB nanozymes were administered to the colitis cellular model. The WB analysis results showed that, compared with the PB, N-PB, and M-PB groups, the upregulation of E-cadherin and Occludin expression was most pronounced in the NM-PB group (Fig. 2J, Fig. S2F-G).

Activated inflammatory macrophages play a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of intestinal colitis [40]. LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages undergo activation characterized by the upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), a hallmark of M1 macrophage polarization, which leads to the production of significant quantities of reactive nitrogen species (RNS), including nitric oxide (NO). These RNS can disrupt mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, resulting in an up to tenfold increase in the release of ROS [41].

To further elucidate the potential of NM-PB nanozymes in promoting the polarization of M1 macrophages towards an M2 phenotype, we conducted cellular immunofluorescence assays. Our findings revealed that PB, N-PB, M-PB, and NM-PB nanozymes exhibited a remarkable ability to attenuate LPS-induced activation of M1 macrophages and downregulate iNOS expression when compared to the LPS group. Additionally, these treatments upregulated the expression of CD206, a surface protein marker associated with M2 macrophages. Notably, NM-PB nanozymes demonstrated the most significant effect in inducing this transition (Fig. 2H-I, Fig. S2H-I).

These findings indicate that NM-PB nanozymes possesses the capability to disrupt the detrimental feedback loop established by ROS and excessive immune response in the colitis cell model, thereby mitigating apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells and restoring intestinal mucosal barrier function. Additionally, it can facilitate the conversion of M1 macrophages into M2 phenotype. This effect may be attributed to the dual-targeting capability of neutrophil-macrophage hybrid membrane, which enhances intracellular accumulation of PB nanozymes and further improves their functional efficacy.

ROS scavenging activity of NM-PB nanozymes and induction of macrophage reprogramming in vitro. A–C) The scavenging effect of NM-PB nanozymes on •OH, •OOH, and H2O2. D–E) Intracellular ROS scavenging capacity of NM-PB nanoenzymes as detected by flow cytometry and CLSM (scale bar = 10 μm). F) Relative mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) in FHC cells treated with different treatments detected by RT-qPCR (n = 3). G) Immunofluorescence staining of TNF-α in FHC cells after different treatments (scale bar = 10 μm). H–I) Immunofluorescence staining of iNOS and CD206 in RAW264.7 cells after different treatments (scale bar = 10 μm). J) Western blot analysis of the expression of E-cadherin, Occludin, Bcl2, and Bax proteins in FHC cells after different treatments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparison test

Assessment of the therapeutic efficacy of PB nanozymes in UC

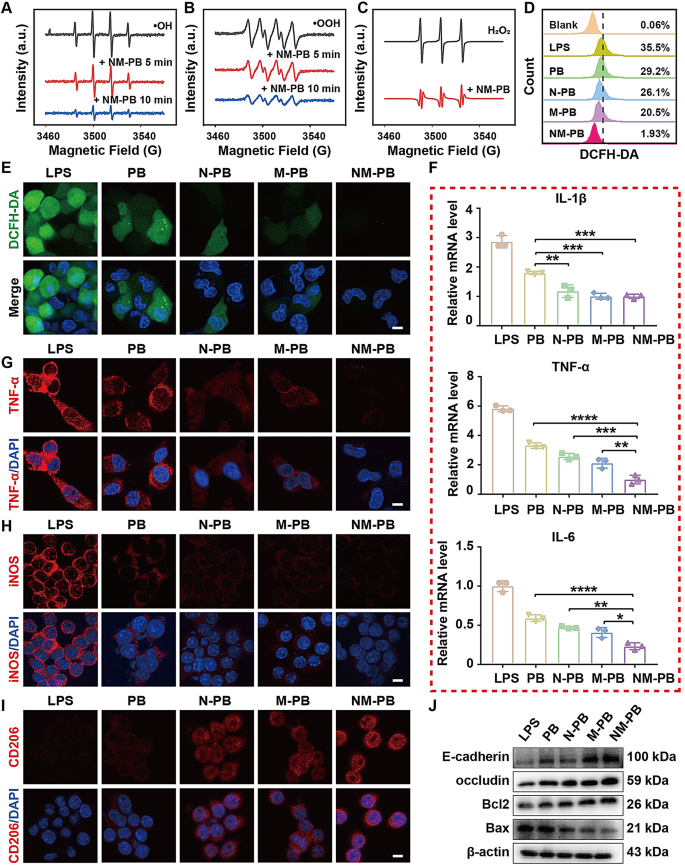

The potent ROS scavenging activity of PB in vitro warrants further investigation into its therapeutic efficacy in a murine model of DSS-induced UC. all mice were randomly divided into five groups (n = 5): G1: PBS group (healthy mice receiving PBS), G2: DSS group (mice with UC), G3: DSS + PB 8 mg/kg group, G4: DSS + PB 20 mg/kg group, G5: DSS + PB 50 mg/kg group. Mice were administered with 3% DSS for five days to induce an acute UC model, followed by intravenous tail injections of PB nanozymes on days 5, 6, and 7. The optimal therapeutic dose of PB nanozymes was determined by treating the UC mouse model with different concentrations of PB nanozymes (8 mg/kg, 20 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg) (Fig. 3A).

To assess the protective effects of PB nanozymes on UC lesions, we measured the body weight, colon length, and disease activity index (DAI) of the mice, utilizing the method described in previous literature [42], and conducted histological examinations of the distal colon. The results depicted in Fig. 3B-E demonstrate that mice treated with varying doses of PB nanozymes exhibited significant improvements in body weight, intestinal tube length, and DAI compared to G2 group. The HE staining results revealed that the crypts of the intestinal tissue in the G2 group exhibited complete distortion, severe loss of goblet cells, and evident infiltration of inflammatory cells (Fig. S2J). In contrast, these pathological changes were mitigated in the G3, G4, and G5 groups. Interestingly, the therapeutic effects of G4 and G5 groups were comparable, with both significantly mitigating inflammatory damage in mice.

Subsequently we investigated the effect of PB nanozymes on the expression of inflammatory cytokines in mice UC model. RT-qPCR analysis revealed that compared to the G2 group, the mRNA expression levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were mitigated in G3, G4, and G5 groups. (Fig. 3F-H). Again, the effects in the G4 and G5 groups were comparable, further supporting the anti-inflammatory efficacy of PB nanozymes in alleviating DSS-induced UC.

To explore whether PB can restore epithelial barrier in mice with UC, varying concentrations of PB (8 mg/kg, 20 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg) were administered to the colitis mouse model. The WB results demonstrated the expression levels of Occludin was significantly upregulated in the G3, G4, and G5 groups, as compared to the G2 group (Fig. 3I, Fig. S2K). Furthermore, the induction of ROS has been associated with increased expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax, which promotes apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells [37]. Following treatment with PB nanozymes, we observed a significant downregulation of Bax and an upregulation of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 (Fig. 3I, Fig. S2L-M). Notably, both the G4 and G5 groups exhibited comparable effects in mitigating apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells.

These findings indicate that PB nanozymes possess the capacity for anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic effects, and restoring the functionality of the intestinal epithelial barrier. Given the comparable efficacy observed between the G4 and G5 groups, we selected a dosage of 20 mg/kg for subsequent in vivo experiments.

Determination of the optimal dosage of PB nanozymes for the treatment of UC model in mice. A) Schematic representation of the experimental protocol employed for UC treatment using PB nanozymes. B) Changes in body weight following various treatments. C) Disease Activity Index (DAI) changes after different treatments. D) Representative images illustrating the macroscopic appearance and H&E staining of colon tissue after different treatments (scale bar = 200 μm). E) Colon length (n = 5). F–H) The expression of mRNAs for TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 was determined by RT-qPCR after different treatments (n = 4). I) The expression of proteins for Occludin, Bcl2, and Bax was analyzed by Western blot after different treatments. ns, not significant. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparison test

Biocompatibility of NM-PB nanozymes

Prior to in vivo application, we assessed the biosafety of NM-PB nanozymes through analysis of hematological markers and histopathology examination of vital organs. The administration of NM-PB nanozymes did not lead to any significant abnormalities in liver function, renal function, or blood routine parameters, as demonstrated in Fig. S3A-F. Furthermore, histological analysis using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining demonstrated no significant pathological alterations in major organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys, following treatment with NM-PB nanozymes (Fig. S3G). The findings validate the complete absorption and metabolism of NM-PB nanozymes after intravenous injection, demonstrating its favorable biosafety profile. This supports their potential for in vivo applications and provides a feasible pathway for translating treatment from animal experiments to clinical applications.

In vivo targeting capability and therapeutic efficacy of NM-PB nanozymes

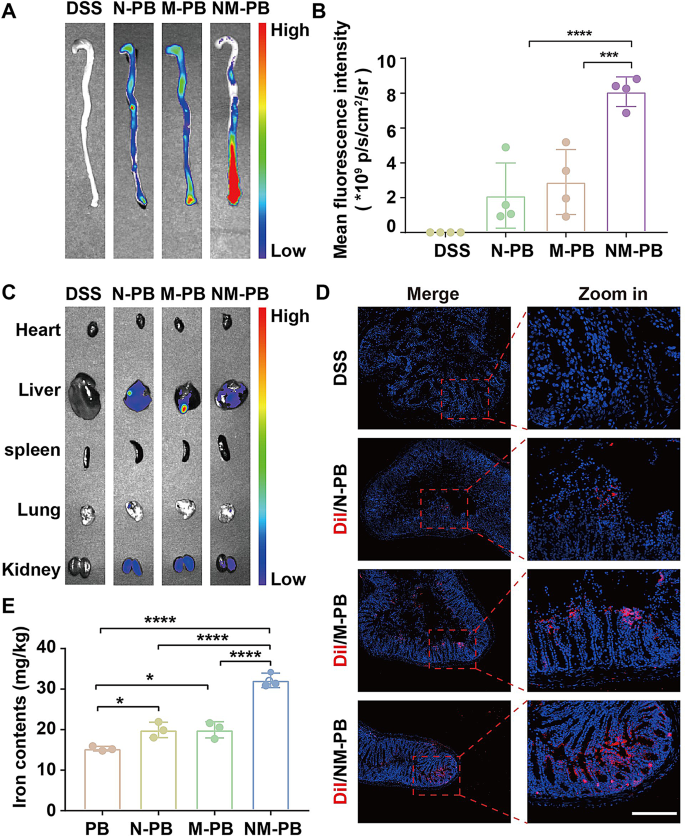

The accurate delivery of nanozymes to UC lesion site is crucial for ensuring therapeutic efficacy. While we have previously demonstrated the in vitro targeting capability of NM-PB nanozymes, the current study focuses on evaluating their localization at UC lesions in a murine model. To facilitate visualization, the cell membranes of the nanozymes were labeled with Dir fluorescent dye. Following the intravenous administration of equimolar amounts of N-PB, M-PB, and NM-PB nanozymes into the mouse UC model, the colons were harvested at 24 h for fluorescence imaging to visualize their distribution. As depicted in Fig. 4A-B, the fluorescence signal was observed to be minimal in the N-PB and M-PB groups, respectively. whereas a robust fluorescence signal was detected in the NM-PB group, indicating the significant targeting capability of the neutrophil-macrophage hybrid membrane. Furthermore, the biodistribution of the injected nanozymes in major organs was also evaluated. Biodistribution analysis revealed fluorescent signals in the liver and kidneys 24 h post-intravenous administration (Fig. 4C, Fig. S4A), suggesting these organs play a role in the clearance of nanozymes during systemic circulation.

The in vivo targeting capability of NM-PB nanozymes to UC lesions was investigated using CLSM subsequently. The cell membrane was labeled with Dil fluorescent dye for CLSM visualization. After a 24 h period following intravenous administration, frozen sections of diseased intestinal tissue were examined using CLSM. A small quantity of red fluorescence signal was detected at the site of colon lesions in both the N-PB and M-PB groups. In contrast, a significant enhancement of signals was observed in the NM-PB group (Fig. 4D, Fig. S4B), corroborating the ex vivo fluorescence imaging results.

The enrichment of nanozymes in intestinal lesions was further quantified by analyzing the iron content using ICP-OES. Compared to the PB, N-PB, and M-PB groups, the NM-PB group exhibited a significantly higher concentration of iron in the diseased intestinal tissues (Fig. 4E), further confirming the superior targeting capabilities of NM-PB nanozymes towards UC lesions. Collectively, these results demonstrate that neutrophil-macrophage hybrid membrane exhibits excellent targeting capability to UC lesions.

In vivo targeting capacity of NM-PB nanozymes. A) Ex vivo fluorescence imaging of colon tissues from each group. B) Quantitative analysis of mean fluorescence intensity in colon tissues (n = 4). C) Ex vivo fluorescence imaging of main organs. D) CLSM images of autofluorescence in colon tissue sections (The blue fluorescence indicates the presence of nuclei, while the red fluorescence corresponds to Dil-labeled N-PB, M-PB, and NM-PB nanozymes; scale bar = 500 μm). E) Quantification of iron concentrations measured by ICP-OES following various treatments (n = 3). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparison test

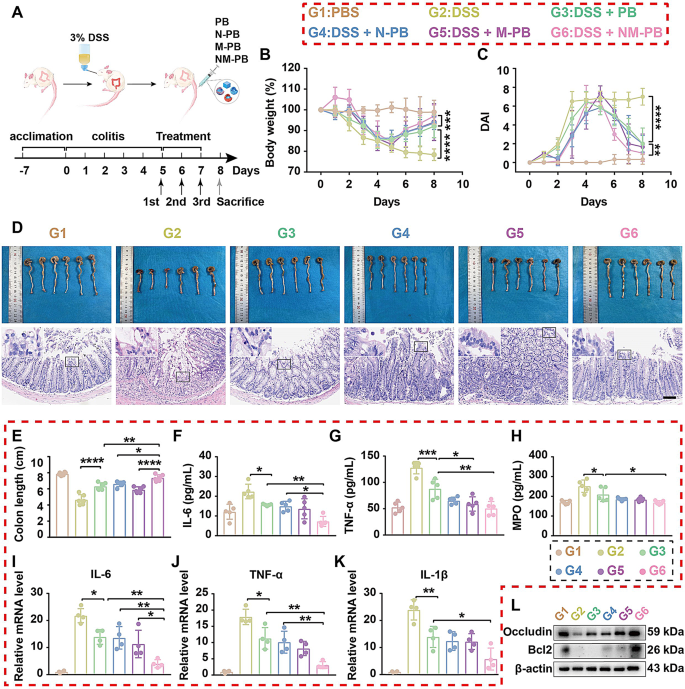

To further compare the therapeutic efficacy of PB, N-PB, M-PB, and NM-PB nanozymes in UC, all mice were randomly divided into six groups: G1: PBS group (healthy mice receiving PBS), G2: DSS group (mice with UC), G3: DSS + PB group, G4: DSS + N-PB group, G5: DSS + M-PB group, and G6: DSS + NM-PB group. The therapeutic efficacy was evaluated by assessing changes in body weight, DAI, colon length, expression levels of proinflammatory cytokines, and histological analysis of colon sections among the groups. Compared to the G2 group, the G3, G4, G5, and G6 groups all demonstrated significantly longer colon lengths, higher body weights, and lower DAI scores (Fig. 5A-E), with the most pronounced improvement observed in the G6 group. The histomorphological analysis of the colon revealed that G2 Group displayed severe crypt destruction, extensive infiltration of immune cells, and significant damage to colonic epithelial cells. In stark contrast, G6 Group displayed nearly normal histological microstructures (Fig. 5D, Fig. S4C). The results demonstrate that the therapeutic modality in the G6 Group significantly ameliorated both the symptoms and histomorphological features of the colitis mice model.

The results from RT-qPCR and ELISA assays demonstrate that, compared to the G2 Group, the G3, G4, G5, and G6 Groups significantly inhibited the expression of inflammatory cytokines IL-6, TNFα, IL-1β, and myeloperoxidase (MPO). Notably, the G6 Group exhibited a superior effect in inhibiting the pro-inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 5F-K). These outcomes can be attributed to the dual-targeting action of NM-PB, which enhances the accumulation of PB at UC lesion sites, thereby significantly enhancing its anti-inflammatory effect.

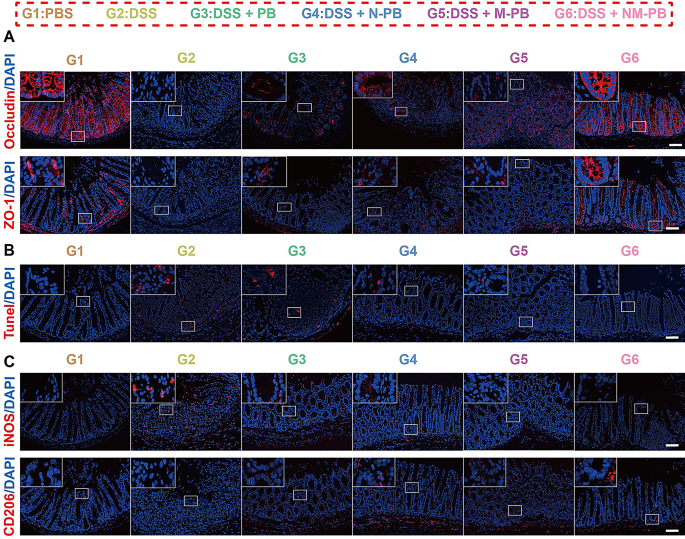

The WB and tissue immunofluorescence analyses revealed that the expression of ZO-1 and Occludin was significantly upregulated in the inflammatory lesions of the G6 group compared to the G3, G4, and G5 groups (Figs. 5L and 6A, Fig. S4D, Fig. S4F-G). These results provide compelling evidence that NM-PB nanozyme treatment enhances the expression of tight junction proteins, facilitating the assembly of tight junction complexes and effectively restoring intestinal barrier function.

Therapeutic efficacy of NM-PB nanozymes in mice UC model. A) Schematic representation of the experimental protocol employed for the treatment of UC using PB, N-PB, M-PB, NM-PB nanozymes. B) Body weight changes after different treatments. C) DAI changes after different treatments. D) Representative images of macroscopic appearance and H&E staining of colon tissues (scale bar = 200 μm). E) Colon length (n = 6). F–H) The levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and MPO as determined by ELISA in the colon tissues after different treatments (n = 5). I–K) The expression of mRNAs for IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β as determined by RT-qPCR in the colon tissues after different treatments. L) The expression of proteins for Occludin and Bcl2 as analyzed by Western blot in the colon tissues after different treatments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparison test

TUNEL staining additionally demonstrated the occurrence of cellular apoptosis in colon tissue. Notably, the red fluorescence intensity associated with TUNEL staining in the G6 group showed a significant decrease compared to the G3, G4, and G5 groups (Fig. 6B, Fig. S4H). Correspondingly, the expression level of Bcl2 protein in the G6 group markedly increased after treatment, indicating that NM-PB nanozymes can effectively alleviate DSS-induced apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells (Fig. 5L, Fig. S4E). Furthermore, the expression of iNOS was significantly downregulated in group G6 compared to groups G3, G4, and G5. In contrast, the expression of CD206 was notably upregulated in the G6 group. These findings indicate that NM-PB nanozymes effectively facilitates the polarization of macrophages from the M1-phenotype to the M2-phenotype, thereby providing protection against oxidative stress for intestinal epithelial cells (Fig. 6C, Fig. S4I-J). The hybrid membrane-modified delivery system utilizes the inflammatory chemotactic properties of neutrophil and macrophage membranes, promoting the accumulation of PB nanozymes in UC lesions. This targeted delivery approach enables the effective exploitation of the diverse functionalities of PB nanozymes, which include anti-inflammatory effects, anti-apoptotic activities, restoration of the intestinal mucosal barrier, and promotion of M1 macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype.

NM-PB nanozymes restore mucosal barrier function and promote macrophage reprogramming in mice with UC. A) Immunofluorescence staining of ZO-1 and Occludin in colon tissues after different treatments (scale bar = 200 μm). B) Representative images of TUNEL staining in colon tissues after different treatments (scale bar = 200 μm). C) Immunofluorescence staining of iNOS and CD206 expression in colon tissues after different treatments (scale bar = 200 μm)

Given the limitations of traditional drugs for treating UC, we compared the biosafety and therapeutic efficacy of NM-PB nanozyme and 5-ASA in a mouse model of UC. all mice were randomly divided into three groups: (1) DSS (mice with DSS-induced colitis without treatment, n = 6), (2) 5-ASA (mice with DSS-induced colitis treated with 5-ASA, n = 5), (3) NM-PB (mice with DSS-induced colitis treated with NM-PB nanozymes, n = 5). The results shown in Fig. S5A-G demonstrate that NM-PB nanozyme and 5-ASA exhibit good biosafety in UC mouse models. Compared to the DSS group, both the 5-ASA and NM-PB groups demonstrated longer colon lengths, higher body weights, and lower DAI scores. Additionally, mice in both the 5-ASA and NM-PB groups displayed nearly normal histological microstructures (Fig. S6A-F), with the most pronounced improvement observed in the NM-PB group. Compared to colitis mice treated with 5-ASA, NM-PB nanozyme is more effective in inhibiting inflammatory responses (Fig. S6G-I), reducing apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells (Fig. S6J, Fig. S7C), restoring the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier (Fig. S6J, Fig. S7A-B), and promoting the polarization of macrophages from an M1-phenotype towards an M2-phenotype (Fig. S7D-E). Therefore, compared to colitis mice treated with 5-ASA alone, NM-PB nanozyme is expected to provide better therapeutic benefits for alleviating UC.

Transcriptomic analysis of the therapeutic mechanism of NM-PB nanozymes in vivo

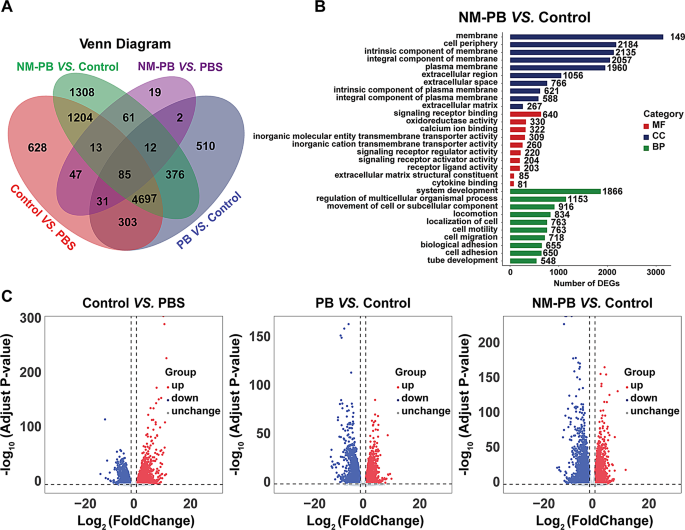

To elucidate the therapeutic mechanism of NM-PB nanozymes in vivo and uncover the molecular mechanisms as well as signaling pathways that contribute to its effectiveness in treating UC, we conducted RNA sequencing on colonic tissues from four experimental groups: PBS group, DSS group, DSS + PB group, and DSS + NM-PB group. The application of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) unveiled distinct transcriptomic profiles among the four groups (Fig. S8A). Additionally, unique transcriptomic characteristics were evident from the Venn diagrams and heatmaps (Fig. 7A, Fig. S8B).

The volcano plot and the bar chart of total DEGs indicate that, compared to the PBS group, the DSS group exhibited 7,008 DEGs, with 4096 genes upregulated and 2912 genes downregulated. After treatment with PB Nanozymes, a total of 6016 DEGs (2627 upregulated genes and 3389 downregulated genes) were identified. Remarkably, following treatment with NM-PB nanozymes, a total of 7756 DEGs were observed, comprising 2959 upregulated genes and 4797 downregulated genes (Fig. 7C, Fig. S8C). Notably, the transcriptome profile of NM-PB-treated mice with UC resembles that of the PBS group.

Subsequently, we performed clustering and enrichment analyses on the DEGs to clarify the therapeutic mechanisms of NM-PB nanozymes. The DEGs were initially categorized into three groups, namely molecular function (MF), biological process (BP), and cellular component (CC), based on the gene ontology database (GO). There were significant differences (p < 0.05) in several biological pathways between the DSS group and NM-PB group, including cytokine binding, oxidoreductase activity, signal receptor binding, and signal receptor regulator activity (Fig. 7B).

RNA-seq analysis of DSS-induced colitis regulated by NM-PB nanozymes. A) Venn diagram illustrating the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified through whole transcriptome RNA-seq analysis among the PBS, DSS, PB, and NM-PB groups (| log2(fold change) | > 1, adjusted P < 0.05). B) GO functional enrichment in NM-PB group Vs. DSS group. C) Volcano plot exhibiting the DEGs in the DSS group Vs. the PBS group (left), in the PB group Vs. DSS group (middle), in the NM-PB group Vs. DSS group (right) from RNA-seq data (up-regulated genes: red; down-regulated genes: blue)

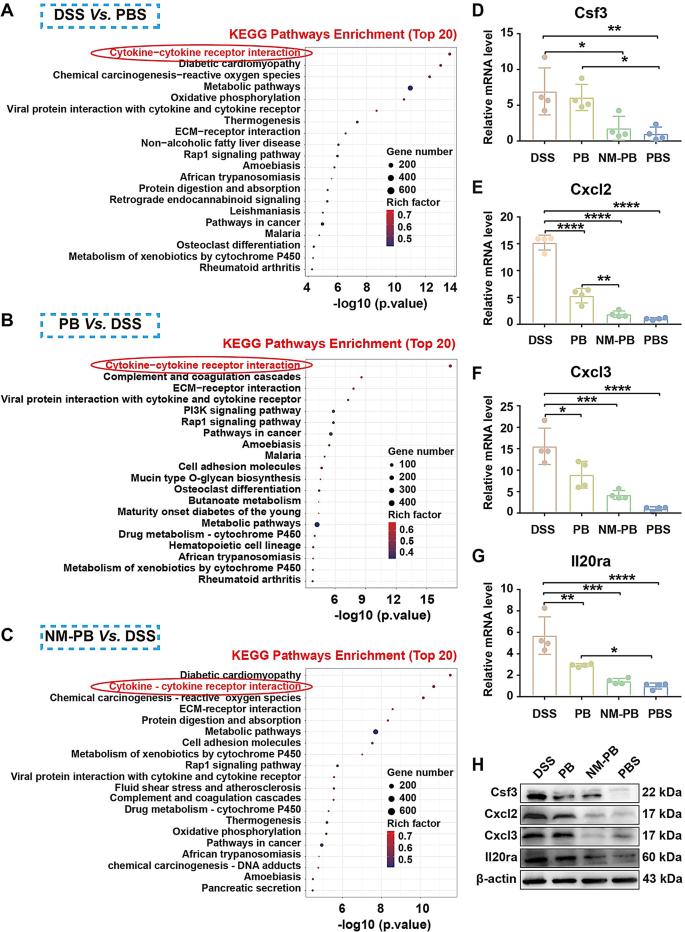

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes database (KEGG) [43] was performed to investigate related items with the log2FC expression level of DEGs as the evaluation standard. Between the DSS group versus PBS group, PB group versus DSS group, and NM-PB group versus DSS group, DEGs were all associated with the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction signaling pathway in KEGG (Fig. 8A-C).

Therefore, we speculate whether NM-PB nanozymes regulate the progression of UC through the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction pathway. Based on the analysis of DEGs data, the expression of key molecules (Cxcl3, Il19, Il20ra) associated with the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction pathway were inhibited (Fig. S8D-F). Results from RT-qPCR and WB experiments consistently confirmed that compared to the DSS group, the expression levels of Cxcl2, Cxcl3, Il20ra, and Csf3 are significantly downregulated after PB and NM-PB treatment, with the NM-PB group exhibiting expression levels close to those of the PBS group (Fig. 8D-H). In summary, NM-PB nanozymes primarily alleviate symptoms in a mouse model of UC by inhibiting the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction pathway. This action disrupts the vicious cycle of inflammation and reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to reduced apoptosis, diminished inflammation, and restored intestinal barrier function.

Therapeutic mechanisms of the NM-PB nanozymes in mice UC model. A–C) KEGG pathways enrichment analysis of DEGs in the DSS group Vs. the PBS group, PB group Vs. the DSS group, and the NM-PB group Vs. the DSS group. D–G) The expression of mRNAs for Csf3, Cxcl2, Cxcl3, and Il20ra as determined by RT-qPCR in the colon tissues after different treatments. H) Validation of the expression of Csf3, Cxcl2, Cxcl3, and Il20ra in colon tissues after different treatments, measured by RT-qPCR and Western blot. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001. one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparison test