Characterization of TiO2-PDMS reactor

The synthesized TiO2-PDMS nanocomposites were characterized to analyze the distribution of the TiO2 nanoparticles and study the optical properties of the fabricated PCR reactors to test their suitability for fluorescence detection. Figure 2a, b show the synthetic scheme of room-temperature curable pristine PDMS and TiO2-PDMS nanocomposites, fabricated to form PCR reactors on the carbon-graphene mixed plasmonic film. For evaluating the surface morphology and composition of the synthesized nanocomposite, samples with pristine PDMS and 0.25 wt% of TiO2 in PDMS were prepared for characterization by optical microscope (Olympus, BX53M), field emission scanning electron microscope, and energy dispersive spectroscopy (FE-SEM/EDS) (Hitachi, S-4800). Initially, the cross-sections of frustums of cone-shaped reactors were imprinted on the plasmonic film, having a PDMS thickness of 30 µm beneath the PCR reaction compartment, and were observed using the optical microscope (Fig. 2c). The samples were characterized by FE-SEM to see the dispersion of nanoparticles in the PDMS, and EDS analysis confirmed the presence of the nanoparticles (Fig. 2d, e). To study the possible effect of surface roughness on the enhancement of heat transfer [40], atomic force microscopy (AFM) (PSIA, XE100) was performed for pristine PDMS, 0.1, and 0.25 wt% of TiO2-PDMS nanocomposites. Each 10 × 10 µm2 area of the samples was analyzed with a scan rate of 0.5 Hz, in non-contact mode. Since the roughness of surfaces affects the cooling rate [41, 42], the root mean square (RMS) surface roughness was observed to increase with the weight percentage of TiO2 in PDMS (Figure S3). The higher the surface roughness, the more the nanoscale cavities that can act as nascent sites for nucleation to enhance the heat transfer rate [43].

To prove the cumulative effects of TiO2 nanoparticles in PDMS upon photoexcitation, Raman (WITec, Alpha300 R) and UV–Vis (Jasco, V-770) absorbance characterizations were conducted on the nanocomposite films. The confocal Raman microscope was used for the non-destructive imaging analysis of the samples, wherein the white light LED acted as the source for Köhler illumination, and a laser wavelength of 532 nm was employed. After dropping 100 µL of the precursor solution, respectively, for pristine PDMS, 0.1, and 0.25 wt% of TiO2-PDMS nanocomposites on the PET substrate, each dropped solution was used to fabricate the film with a thickness of 7 µm by a spin coater at 1000 rpm for 1 min, and then dried at room-temperature. Raman spectra were observed by enhancing the material’s chemical fingerprint through the distinct physical stretching and vibrational modes due to the interaction between the PDMS matrix and TiO2 nanoparticles [44]. The spectra for pristine PDMS, 0.1 and 0.25 wt% of TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite were acquired using an excitation wavelength of 595 nm at room-temperature using a Raman spectrometer. The TiO2-PDMS showed a noticeable enhancement of Raman peak intensities, specifically Si–O stretching at 488 cm−1 since the spectrum intensity of PDMS can be enhanced by the induced scattering of nanoparticles (inset in Fig. 2f) [45]. In addition, the UV–Vis absorbance of the TiO2-PDMS reactor upon the addition of nanoparticles was determined to see whether the wavelength range of emitted fluorescence from the PCR probes overlapped with the absorbance of the TiO2-PDMS reactor. The pristine PDMS does not absorb most of the light from 300 to 1000 nm of wavelength range, whereas the light absorption increased as the nanoparticles concentration in PDMS increased. Based on the attained absorbance and transmittance characteristics of pristine PDMS, 0.1 and 0.25 wt% TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite samples (Fig. 2g and S4), there were no serious overlapping issues between TiO2-PDMS reactor and the PCR probes. Furthermore, we can predict a correlation between light absorption and heat transfer to the surrounding medium by the nanoparticles. The nanoparticles’ higher incident light absorbance, as shown in Fig. 2g, indicates enhanced heat transfer. Based on the Raman and UV–Vis studies, the emitted fluorescence intensity can be postulated to be enhanced by the reflection effect of TiO2 nanoparticles with the excitation and emission ranges of the PCR probes.

Thermal properties of TiO2-PDMS reactor

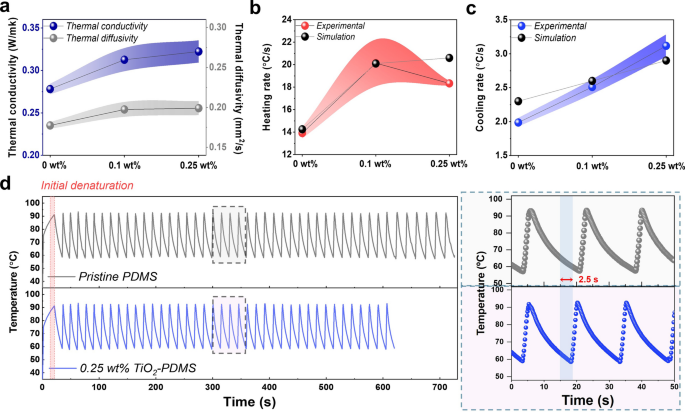

To analyze the changes in the heat transfer throughout the PCR reactor upon the addition of thermally conductive TiO2 nanoparticles in PDMS, computational models were used to optimize the thermal performance based on their thermal conductivity under various composition ratios. To calculate the thermal conductivity for different compositions of the TiO2-PDMS nanocomposites, the thermal diffusivity and heat capacity of the reactors were measured. For this analysis, pristine PDMS, 0.1 and 0.25 wt% of TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite blocks with a thickness of 1.5 mm were fabricated. The laser flash analysis (LFA) (NETZSCH, LFA467) was used as the thermal diffusivity measurement technique (Fig. 3a). Five random positions were chosen on the sample for the measurements, and the laser was irradiated in a direction normal to the plane of the sample, with 230 V and 0.3 ms of the pulse width. A differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) (NETZSCH, DSC214) was used to calculate the specific heat capacity of the samples, using a N2 purge gas flow rate of 20 mL/min at 24 °C. For three different PDMS systems, the heating and cooling rates were calculated using the 940 nm wavelength light which were optimized in previous studies [19], and the energy model with \(k\) = 0.27, 0.312 and 0.322 W/mK, respectively (Figures S5), as obtained from the thermal diffusivity analysis. Further, experiments were carried out using different fractions of nanocomposites to study the actual phenomena and observe the target gene amplification. A two-step thermal cycle was applied to analyze the amplification efficiency of pristine PDMS, 0.1 and 0.25 wt% of TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite reactors for the photonic qPCR. The PCR solution of 1 µL was assumed to be inside the reactor covered with 4 µL of mineral oil to prevent evaporation during the thermal cycles. As the LED is switched on, the temperature of the PCR mixture is reached to denaturation temperature (~ 93 °C), and the software detects and sends a signal to switch off the LED power automatically. The ON–OFF sequence continues for 40 thermal cycles. Initial denaturation occurs at 90–93 °C for 5 s, followed by denaturation at 91–93 °C, and annealing at 57–58 °C based on target amplicon size and primer conditions. The heating and cooling data obtained from the photonic PCR were compared with the numerical results, and the findings indicate that thermal cycling data corresponds well with the simulation results, with an error of ± 0.86 °C/s and ± 0.21 °C/s, respectively (Fig. 3b, c). The cooling rates increased to 0.25 wt% of the TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite reactor. However, after loading 0.25 wt% of TiO2, the heating and cooling rates reduced gradually (Figure S6) postulated due to the aggregation and non-uniform dispersion of the nanoparticles in the PDMS matrix. The total time taken for the target gene amplification with the fabricated 0.25 wt% of TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite reactor was approximately 100 s faster than the pristine PDMS reactor (Fig. 3d). Since the thermal conductivity increased as the weight percentage of the TiO2 nanoparticles increased, 40 thermal cycles were completed in 620 s leading to exponential amplification of the targeted sequences.

Comparison of a thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivities, numerical and experimental data (6 sets of samples at 3 different concentrations) for b heating and c cooling rates as a function of TiO2 loading ratio, and d thermal cycling data from the photonic PCR, for pristine PDMS and 0.25 wt% of TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite reactors; inset shows the comparison of each thermal cycling times for showing enhancing cooling ramp from each cycle

DNA amplification in TiO2-PDMS PCR reactor

As fluorescent dyes (SYBR Green) bind to the minor groove of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) in the annealing step, they emit fluorescence when they are bound to dsDNA only. Thus, the fluorescence intensity increases proportionally as the number of amplicons increases [46, 47]. Therefore, it is essential to improve selective fluorescence signals in sequence-specific DNA detection and quantification [3, 48]. To enhance the fluorescence signal in the photonic qPCR, fluorescence intensities were compared for each sample: pristine PDMS, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 wt% of TiO2-PDMS reactors in the photonic PCR. While performing qPCR, the fluorescence intensity values at every 5th cycle were compared through the fluorescence camera equipped with the filter. As the TiO2 nanoparticles surrounding the excited fluorophore possess a higher refractive index than pristine PDMS, the fluorescence intensity was increased (Figure S7). Also, the fluorescence brightness gradually enhances upon the addition of TiO2 nanoparticles in the pristine PDMS (Figure S7). This emitted fluorescence scintillates to TiO2 nanoparticles present at the matrix interface, which can reflect and further enhance the fluorescence [36]. Based on the experimental results (Fig. 3 and S6), the TiO2 composition was optimized at 0.25 wt% for fabricating the PCR reactors based on thermal cycling efficiency and distinct threshold cycle (Ct) value. The enhancement of fluorescence intensity via the TiO2-PDMS reactors was further proved by simply transferring 1 µL of the amplified PCR solution (1 copy/25 µL) using the benchtop qPCR (34, 36, 40 and 45 thermal cycles, respectively) into both the pristine PDMS and TiO2-PDMS reactors (Figure S8). The fluorescence intensity from the amplified samples of the 34 cycles was brighter in the TiO2-PDMS reactor while very dim fluorescence was observed from the pristine PDMS reactor.

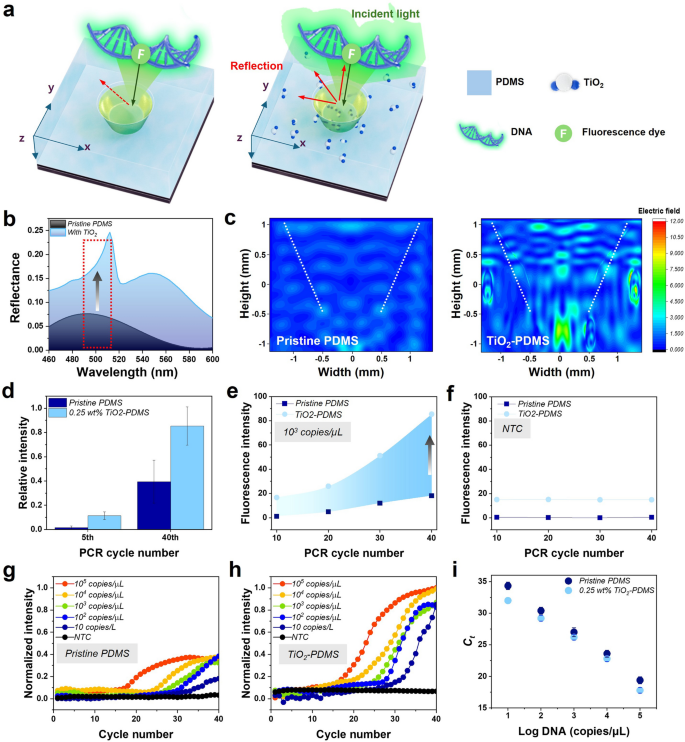

The fluorescence enhancement using the TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite reactors in the photonic PCR was summarized in Fig. 4. The PCR reactor with and without TiO2 was simulated based on the refractive index using an electric field to confirm fluorescence signal enhancement, and the increase in reflectance when TiO2 is present in PDMS (Fig. 4a, c). The reflectance with TiO2 in PDMS doubled compared to without TiO2 (Fig. 4b) [49, 50]. Electric field intensity distribution and reflectance, as depicted in Fig. 4b, c, were computed utilizing the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method with ANSYS LUMERICAL (Version-2018a, ANSYS, Inc). The refractive indices for PDMS and the PCR solution are 1.4 and 1.33, respectively [51]. A linearly polarized plane wave source, with electric field oscillations along the z-direction and a spectral range from 450 to 600 nm, was employed for top-side illumination of the structure at normal incidence. Two power monitors were positioned, one behind the light source and the other in the y-direction of the structure plane, capturing reflectance signals and electric field distributions, respectively, at the same spectral interval and frequency points with respect to the source. All boundaries of the simulation region are set to perfectly matched layers.

Photonic PCR results by using pristine PDMS and 0.25 wt% of TiO2-PDMS PCR reactors. a A numerical model of electric field distribution in a PDMS reactor with the presence of the fluorescent dye and TiO2. The particle size is typically 200 nm, b variation in reflectance between PDMS and TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite reactors obtained from full-wave electromagnetic simulations, c intensity of electric field distribution as obtained from simulation in pristine PDMS and TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite reactor with the presence of fluorescence dye. d, e Fluorescence amplification graphs of the 10th, 20th, 30th, and 40th cycles with the 103 copies/µL of λ-DNA and NTC, f comparison of relative fluorescence intensities between the 5th and 40th cycle from 103 copies/µL of λ-DNA amplification (18 experiments were conducted) in pristine PDMS and TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite PCR reactors, respectively. g, h Normalized quantification graph of various target concentrations of pristine PDMS reactors and TiO2-PDMS reactors, respectively. i Standard curves of the Ct values versus the log concentration of λ-DNA. All the standard deviations are shown as error bars

To elucidate the underlying principles of fluorescent enhancement, the following equation (Eq. 2) is used, where fluorescence enhancement is denoted as \({\eta }_{F}\), the product of gains in excitation intensity enhancement as \({\eta }_{exc}\), quantum yield \({\eta }_{\phi }\), and collection efficiency \({\eta }_{coll}\). The fluorescence quantum yield quantifies the ratio of emitted photons to absorbed photons. Furthermore, the quantum yield gain can be expressed as the ratio between the gain in the radiative rate\(\eta_{\Gamma rad}\) and the total decay rate \(\eta_{\Gamma tot}\) [49].

$$ \eta_{F} = \eta_{exc} \eta_{coll } \eta_{\Gamma rad} /\eta_{\Gamma tot} $$

(2)

To extract the enhancement of fluorescent signal in PDMS with and without TiO2 nanoparticles, the quantum yield gain should be around 1 \(\left( {\eta_{\Gamma rad} /\eta_{\Gamma tot} \sim 1} \right)\), due to the large size of the inverted frustum of the cone-shaped well [50]. Finally, the fluorescent enhancement equation can become \({\eta }_{F}={\eta }_{exc} {\eta }_{coll }\approx {(\frac{\left|E\right|}{\left|{E}_{0}\right|})}^{4}\), where \(E\) is the electric field amplitude in TiO2-PDMS and \({E}_{0}\) is the electric field amplitude in PDMS. The numerical simulation of reflectance spectra corresponding to the reactor model proves that the TiO2-PDMS shows higher relative reflectance and with the quantum yield gain as 1, the excitation light can be confined in PCR solution more effectively (Fig. 4b). The photothermal substrate used in the device can contribute to electromagnetic field enhancements, such as sacttering or local field effects, especially when part of a composite material.

To verify specific amplification, 40 thermal cycles of PCR involving λ-DNA target sample and negative template control (NTC) were performed and after completing the PCR reaction, the samples were collected and performed gel electrophoresis to confirm the absence of non-specific amplicons (Figure S9). In the case of 0.25 wt% of TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite PCR reactors, it was observed that the average fluorescence signal at the 10th and 40th cycle was up to 2 times brighter than the pristine PDMS reactors (Fig. 4d). On the other hand, in the NTC sample, no fluorescence signal change was observed from the 10th to the 40th thermal cycles (Fig. 4e). This suggests that the fluorescence enhancement effect is solely attributed by TiO2, without any other influencing factors. The 5th and 40th cycle fluorescence intensity is shown in Fig. 4f using the template concentration of 103 copies/µL in pristine PDMS and 0.25 wt% of TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite PCR reactors, respectively. During annealing, the fluorescent dye emits a stronger fluorescence, postulated to be reflected by TiO2 nanoparticles in the PDMS. Figure 4g, h shows the normalized intensity of PCR amplification curves for each concentration of template using pristine PDMS and 0.25 wt% of TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite reactors to characterize PCR amplification. The same volume of PCR solution with different concentrations (copies/µL) was successfully amplified and confirmed through gel electrophoresis (Figure S10). Figure 4i represents the Ct value according to the log concentration of λ-DNA with the existing reactor to confirm the reproducibility of experiments. The Ct value of 0.25 wt% of TiO2-PDMS reactors for 5 different λ-DNA concentrations (10 to 105 copies/µL) was about 2 times faster as compared to the pristine PDMS reactors. The attained enhancement effect in fluorescence signal can be explained based on the specular/diffuse reflectance of light [52, 53]. The polymers, in general, and PDMS have low values of refractive index, resulting in low reflectance and low fluorescence collection efficiency. TiO2 nanoparticles, on the other hand, have a high refractive index, making them ideal additives for applications involving enhanced fluorescence signal detection. Furthermore, the optical characteristics of TiO2 nanoparticles in the PDMS material were enhanced by efficiently reflected visible light, and improved light collection within the reactor. However, at a composition of above 0.5 wt% of TiO2 loading, the qPCR graph became close to linear, making it difficult to distinguish Ct. This suggests that more than 0.5 wt% of TiO2-PDMS nanocomposite reactor is not suitable for real-time fluorescence detection due to the low limit of quantitation (LoQ).