Is permanent storage the only strategy for dealing with nuclear waste? It appears not. With the aid of new EU funding, a new project aims to investigate the options for recycling some elements of nuclear waste using novel separation techniques.

For the next three years, 2.3 million euros in funding will support the project “MaLaR – Novel 2D-3D Materials for Lanthanide Recovery from nuclear waste”. The partners comprise groups in Germany, France, Sweden and Romania.

The materials to be recycled are lanthanides, a group of chemical elements which include some rare earths. They are widely used, for example, in screens, batteries, magnets, contrast media and biological probes.

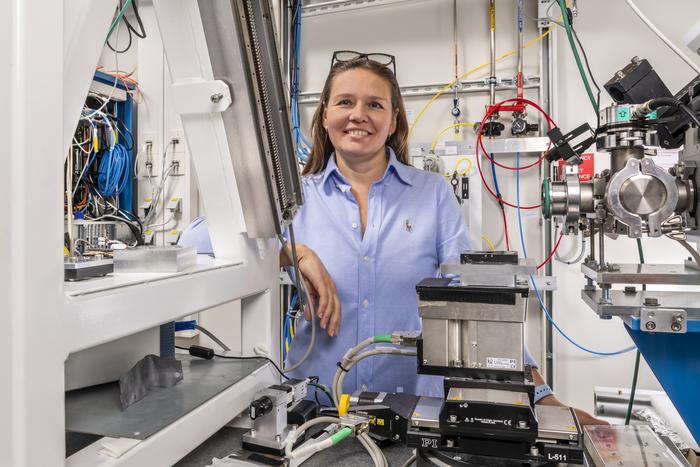

“Lanthanides are a very rare raw material, most of which comes from China. That’s why we are trying to recycle this raw material from waste, even from nuclear waste,” said Professor Kristina Kvashnina of the Helmholtz-Zentrum-Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR), and the coordinator of the MaLaR Project. A physicist, she belongs to HZDR’s Institute of Resource Ecology and holds a professorship at the Université Grenoble Alpes in France.

In order to recycle waste, it has to be separated. Apart from the basic safety risks associated with radioactive elements, there is a special problem with nuclear waste: The materials it contains exhibit very similar chemical reactions. “That’s why it’s very difficult to find something which only causes a reaction in one element and not in others so that you can extract just the one,” explains Kvashnina. Existing separation processes often involve dangerous chemicals, use a great deal of energy and result in additional waste streams.

Carbon materials as specific element scavengers

The MaLaR Consortium aims to develop novel three-dimensional materials for effective, environmentally friendly, sustainable separation methods, applied to both nuclear waste and industrial waste. For example, waste from radiomedical applications. As with existing separation methods, the researchers are working with the principle of sorption. Specific radioactive elements in liquid nuclear waste attach themselves to the neighbouring solid phase of a sorbent and can thus be separated from the rest of the waste.

In recent years, studies have shown that graphene oxides – carbon-based porous materials – can significantly outperform the most important industrial sorbents or radio nuclides currently in use. Moreover, it recently emerged that certain changes in the electronic structure further increase sorption performance. In the MaLaR project, Kvashnina and her partners want to systematically explore the underlying chemical reactions and develop new materials based on graphene oxide that can serve as specific element scavengers.

Getting a grip on nuclear and industrial waste

“Our aim is to design a material with which we can initially extract individual elements from synthetic element mixtures. In the future, that could then be transferred to various applications. Admittedly, in three years we can only take the first step toward recycling, but if we are successful, applications will be within easy reach.”

The impact would be enormous because these novel separation methods would not only help with the recovery of raw materials from nuclear and other industrial waste, but also with the safe final storage of highly radioactive waste. For example, if isotopes with different lifetimes can be separated and then stored separately. The project explicitly aims to develop appropriate close-to-the-market technological solutions.

The MaLaR project draws upon its partners’ expertise in several different fields: 2D/3D materials development, fundamental physics and the chemistry of radioactive elements, as well as with the possibility of using a new in-situ method for the time-resolved investigation of the tiniest concentrations of lanthanides in radioactive materials.

“It’ll be great to spend the next few years working in this team. We can combine fundamental insights from experiments with theoretical calculations and models as well as material characterization and development,” said Kvashnina. As part of the project, she will also be in charge of experiments at HZDR’s Rossendorf Beamline (ROBL) at the European Synchrotron (ESRF) in Grenoble where the new materials will be tested for their chemical properties using intensive x-ray light.

The MaLaR project started on 1 January, 2025. Via the European EURATOM Program, HZDR and the following partners will receive 2.3 million euros over a period of three years:

- Marcoule Institute in Separation Chemistry, University of Montpellier and Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in France

- Universities of Umeå and Uppsala in Sweden

- University POLITEHNICA of Bucharest in Romania

At HZDR, most of the work will be conducted in an alpha-lab in Dresden-Rossendorf and at the ROBL Beamline in Grenoble.