Security professionals are always on the lookout for evolving threat techniques. The Sophos X-Ops team recently investigated phishing attacks targeting several of our employees, one of whom was tricked into giving up their information.

The attackers used so-called quishing (a portmanteau of “QR code” and “phishing”). QR codes are a machine-readable encoding mechanism that can encapsulate a wide variety of information, from lines of text to binary data, but most people know and recognize their most common use today as a quick way to share a URL.

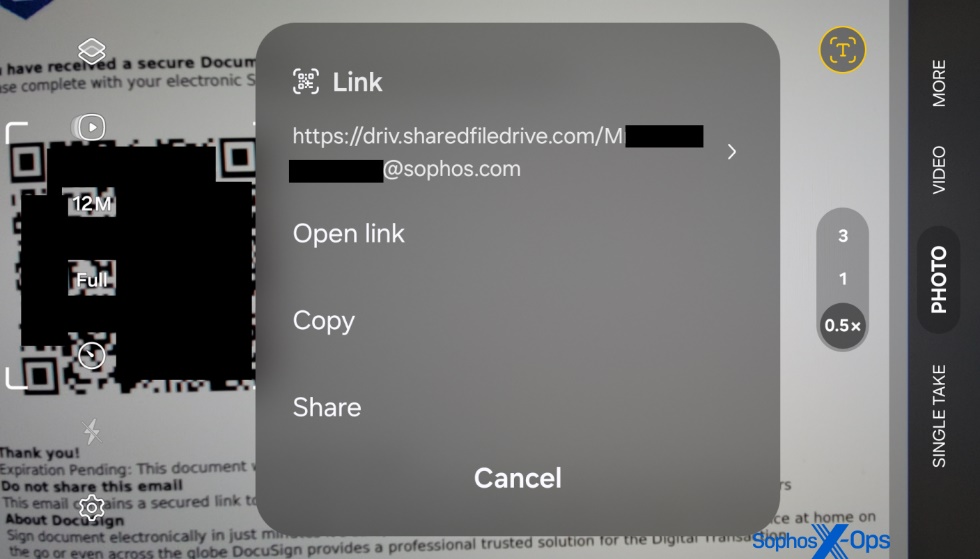

We in the security industry generally teach people resilience to phishing by instructing them to carefully look at a URL before clicking it on their computer. However, unlike a URL in plain text, QR codes don’t lend themselves to scrutiny in the same way.

Also, most people use their phone’s camera to interpret the QR code, rather than a computer, and it can be challenging to carefully scrutinize the URL that momentarily gets shown in the phone’s camera app – both because the URL may appear only for a few seconds before the app hides the URL from sight, and also because threat actors may use a variety of URL redirection techniques or services that conceal or obfuscate the final destination of the link presented in the camera app’s interface.

How the quishing attack works

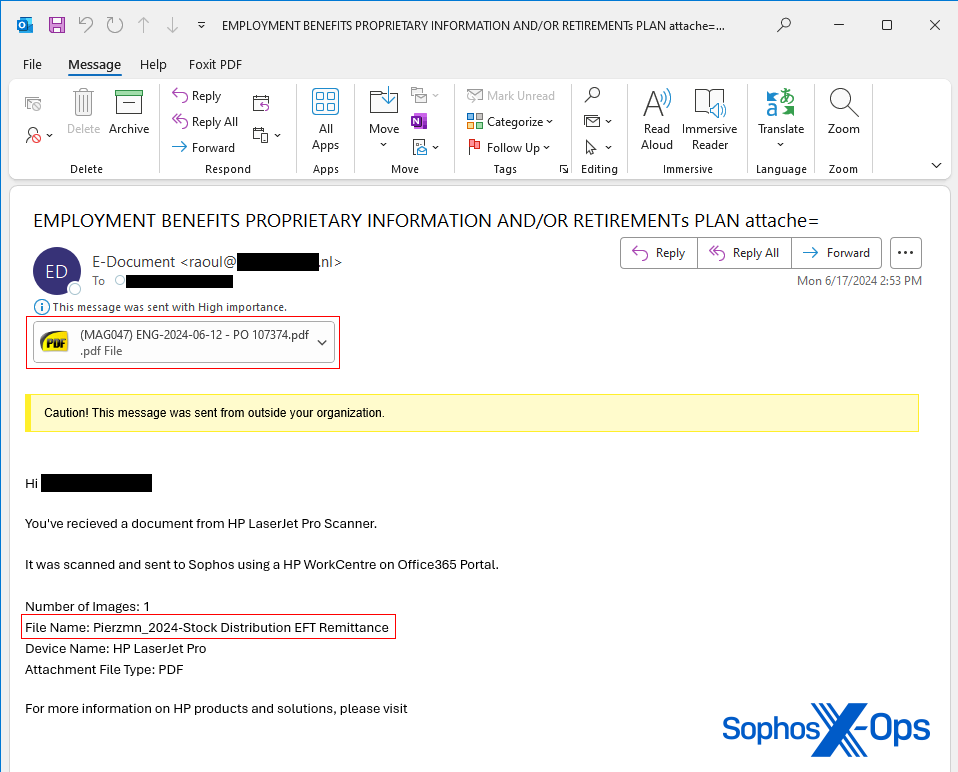

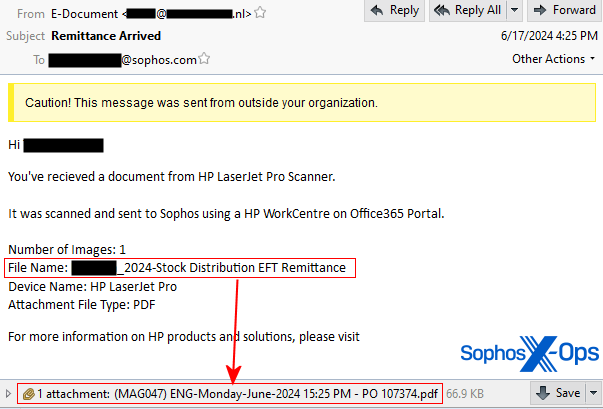

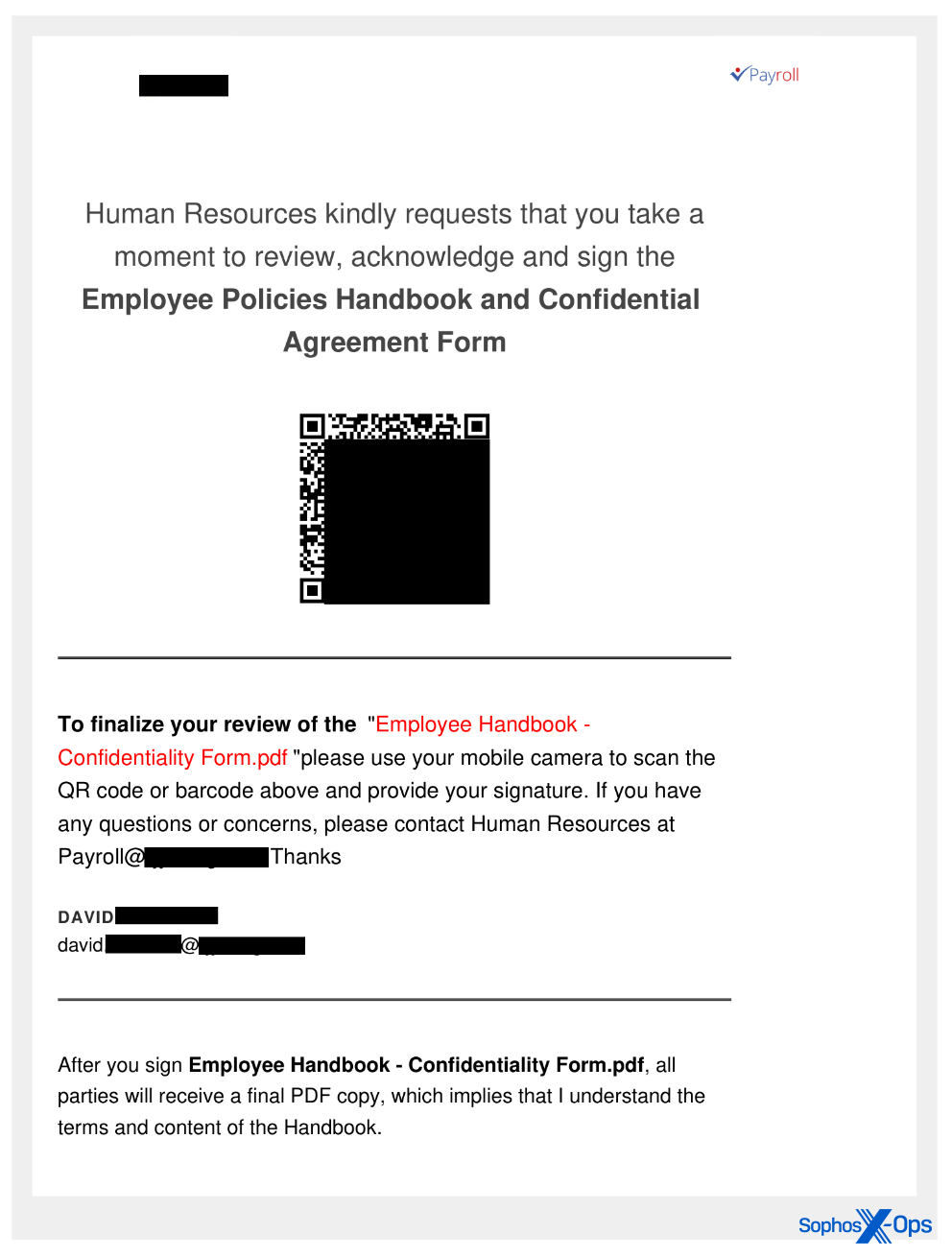

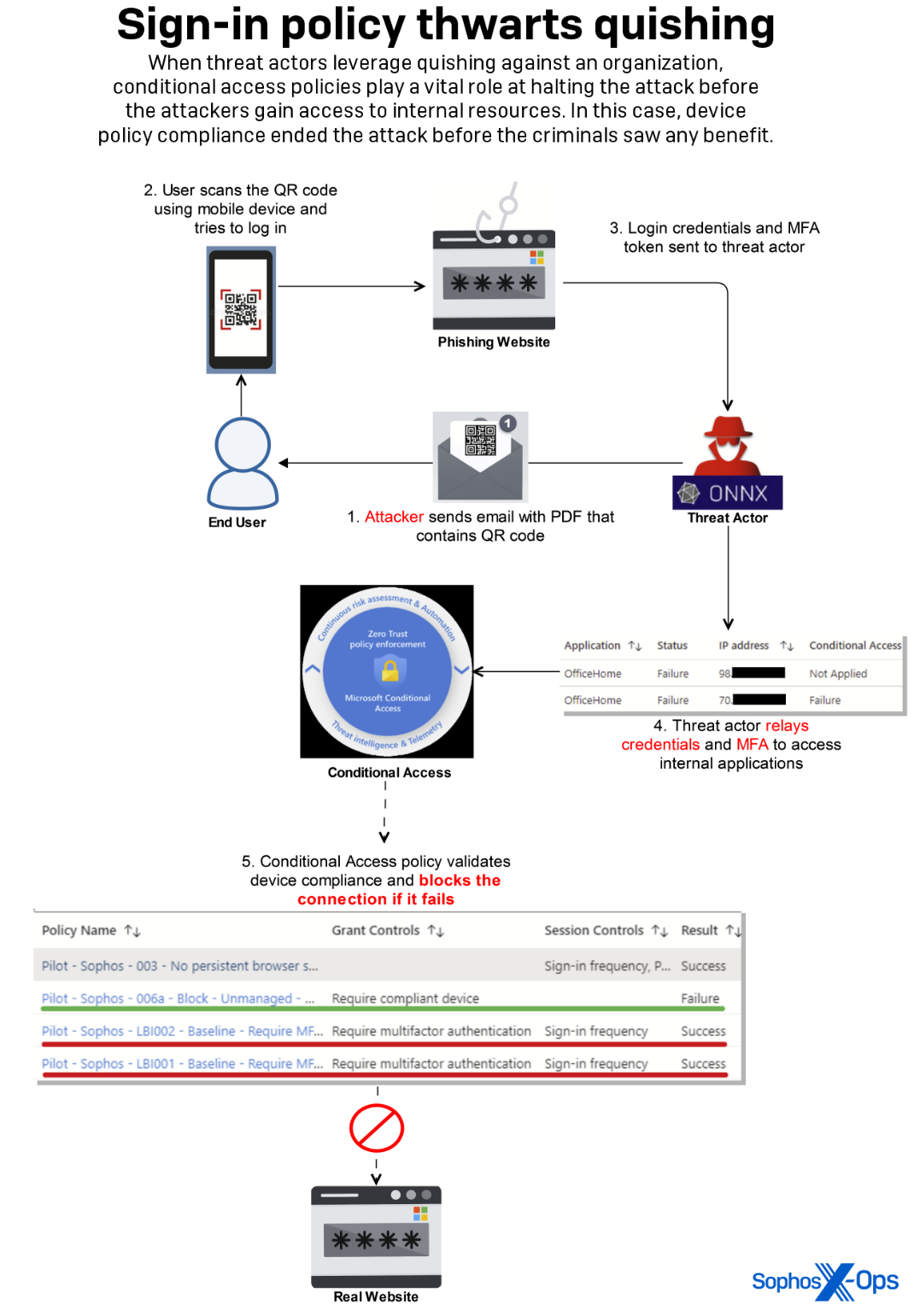

Threat actors sent multiple targets within Sophos a PDF document containing a QR code as an email attachment in June 2024. The spearphishing emails were crafted to appear as legitimate emails, and were sent using compromised, legitimate, non-Sophos email accounts.

(To be clear, these were not the first quishing emails we had seen; Employees were targeted with a batch in February, and again in May. Customers have been targeted by similar campaigns going back at least a year. X-Ops decided to focus on the Sophos-targeted attacks because we have full permission to investigate and share them.)

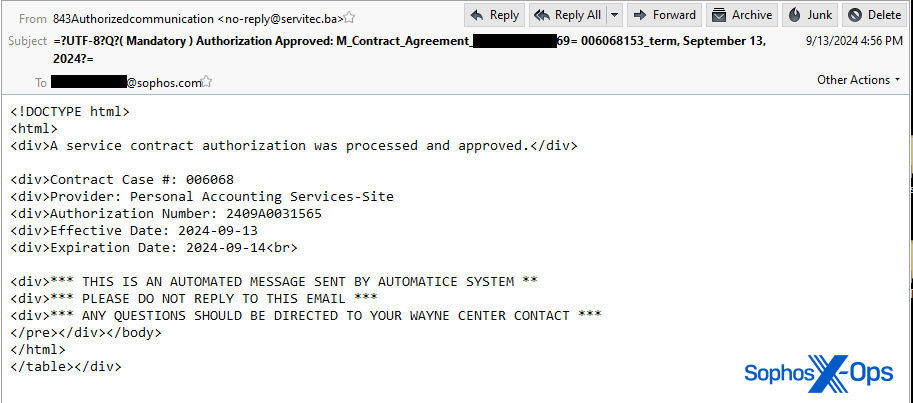

The messages’ subject lines made them appear to originate within the company, as a document that was emailed directly from a networked scanner in an office.

One notable red flag is that the email message that purported to originate from a scanner had a filename for the document in the body of the message that, in all of the messages we received that day, did not match the filename of the document attached to the email.

In addition, one of the messages had a subject line of “Remittance Arrived,” which an automated office scanner would not have used, since that’s a more generalized interpretation of the content of the scanned document. The other message had a subject line of “Employment benefits proprietary information and/or retirements plan attache=” that appeared to be cut off at the end.

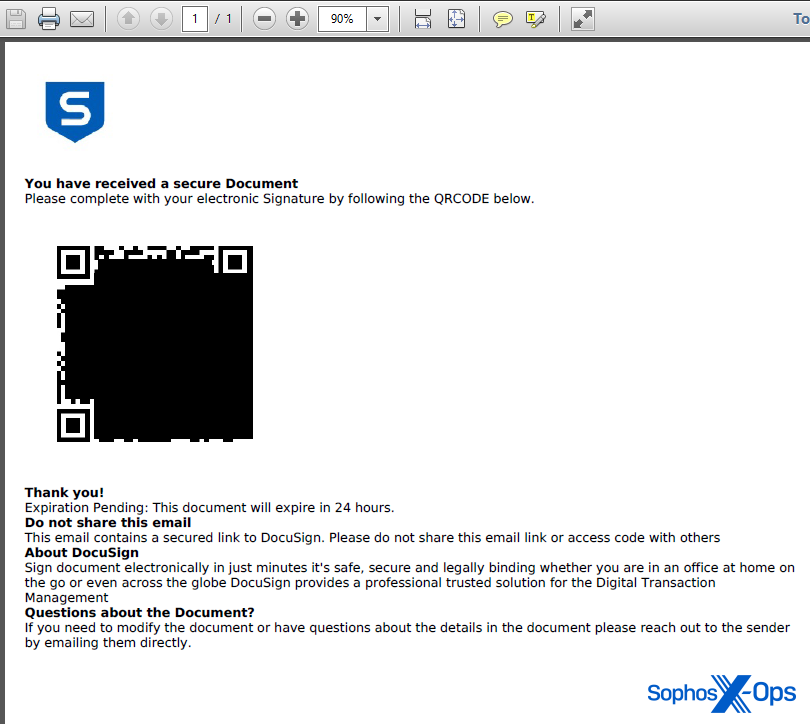

The PDF document contained a Sophos logo, but was otherwise very plain. Text that appears below the QR code states “This document will expire in 24 hours.” It also indicates the QR code points to Docusign, the electronic contract signature platform. These characteristics lend the message a false sense of urgency.

When targets scanned the QR code using their phones, the targets were directed to a phishing page that looks like a Microsoft365 login dialog box, but was controlled by the attacker. The URL had a query string at the end that contained the target’s full email address, but curiously the email address had an apparently random, different capital letter prepended to the address.

This page was designed to steal both login credentials and MFA responses using a technique known as Adversary-in-The-Middle (AiTM).

The URL used in the attack was not known to Sophos at the time the email arrived. In any case, the target’s mobile phone had no feature installed on it that would have been able to filter a visit to a known-malicious website, let alone this one, which had no reputation history associated with it at the time.

The attack successfully compromised an employee’s credentials and MFA token through this method. The attacker then attempted to use this information to gain access to an internal application by successfully relaying the stolen MFA token in near real-time, which is a novel way to circumvent the MFA requirement that we enforce.

Internal controls over other aspects of how the network login process works prevented the attacker from gaining any access to internal information or assets.

As we’ve previously mentioned, this type of attack is becoming more commonplace among our customers. Every day we’re receiving more samples of novel quishing PDFs targeting specific employees at organizations.

Quishing as a service

The targets received emails sent by a threat actor that closely resemble similar messages sent using a phishing-as-a-service (PhaaS) platform called ONNX Store, which some researchers assert is a rebranded version of the Caffeine phishing kit. The ONNX Store provides tools and infrastructure for running phishing campaigns, and can be accessed via Telegram bots.

The ONNX Store leverages Cloudflare’s anti-bot CAPTCHA features and IP address proxies to make it more challenging for researchers to identify the malicious websites, reducing the effectiveness of automated scanning tools and obfuscating the underlying hosting provider.

The ONNX Store also employs encrypted JavaScript code that decrypts itself during the webpage load, offering an extra layer of obfuscation that counters anti-phishing scanners.

Quishing a growing threat

Threat actors who conduct phishing attacks that leverage QR codes may want to bypass the kinds of network protection features in endpoint security software that might run on a computer. A potential victim might receive the phishing message on a computer, but are more likely to visit the phishing page on their less-well-protected phone.

Because QR codes are usually scanned by a secondary mobile device, the URLs people visit can bypass traditional defenses, such as URL blocking on a desktop or laptop computer that has endpoint protection software installed, or connectivity through a firewall that blocks known malicious web addresses.

We spent a considerable amount of time researching our collection of spam samples to find other examples of quishing attacks. We found that the volume of attacks targeting this specific threat vector appear to be increasing both in volume and in the sophistication of the PDF document’s appearance.

The initial set of quishing attachments in June were relatively simplistic documents, with just a logo at the top, a QR code, and a small amount of text intended to create an urgency to visit the URL encoded in the QR code block.

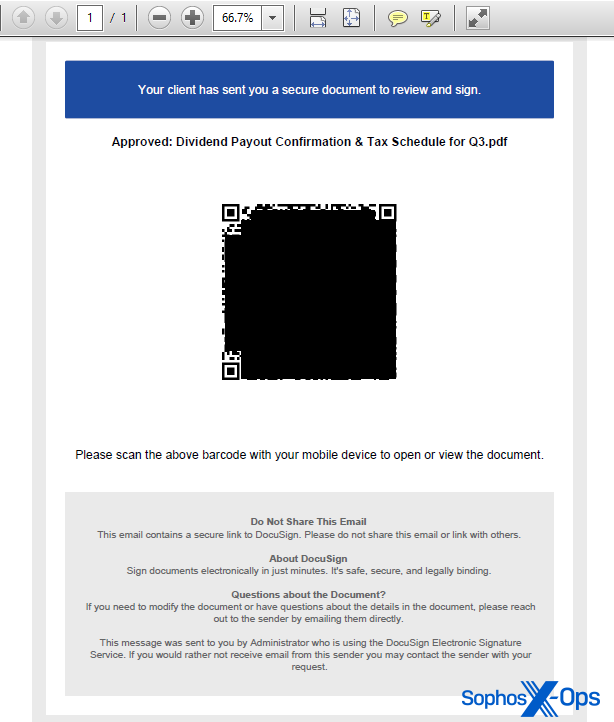

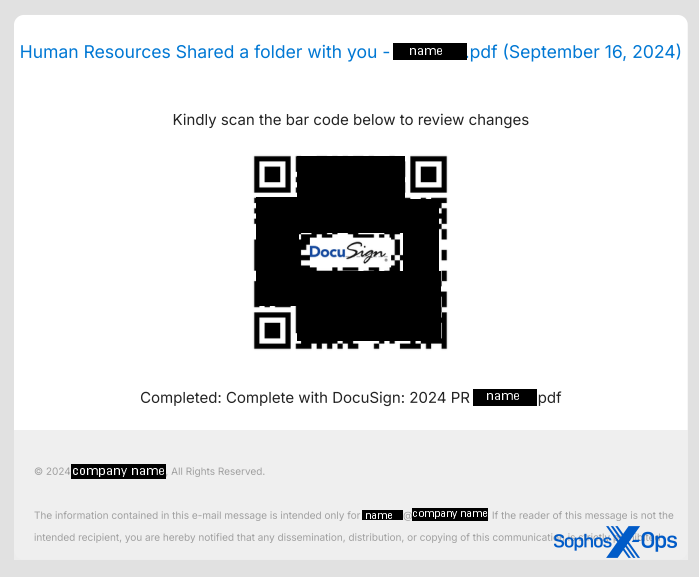

However, throughout the summer, samples have become more refined, with a greater emphasis on the graphic design and appearance of the content displayed within the PDF. Quishing documents now appear more polished than those we initially saw, with header and footer text customized to embed the name of the targeted individual (or at least, by the username for their email account) and/or the targeted organization where they work inside the PDF.

QR codes are incredibly flexible, and part of the specification for them means that it’s possible to embed graphics in the center of the QR code block itself.

Some of the QR codes in more recent quishing documents abuse Docusign’s branding as a graphic element within the QR code block, fraudulently using that company’s notability to social engineer the user.

To be clear, Docusign does not email QR code links to customers or clients who are signing a document. According to DocuSign’s Combating Phishing white paper (PDF), the company’s branding is abused frequently enough that the company has instituted security measures in its notification emails.

To be clear, the presence of this logo inside of the QR code cannot convey any legitimacy to the link it points to, and should not lend it any credibility. It is merely a design feature of the QR code specification, that graphics can appear in the center of them.

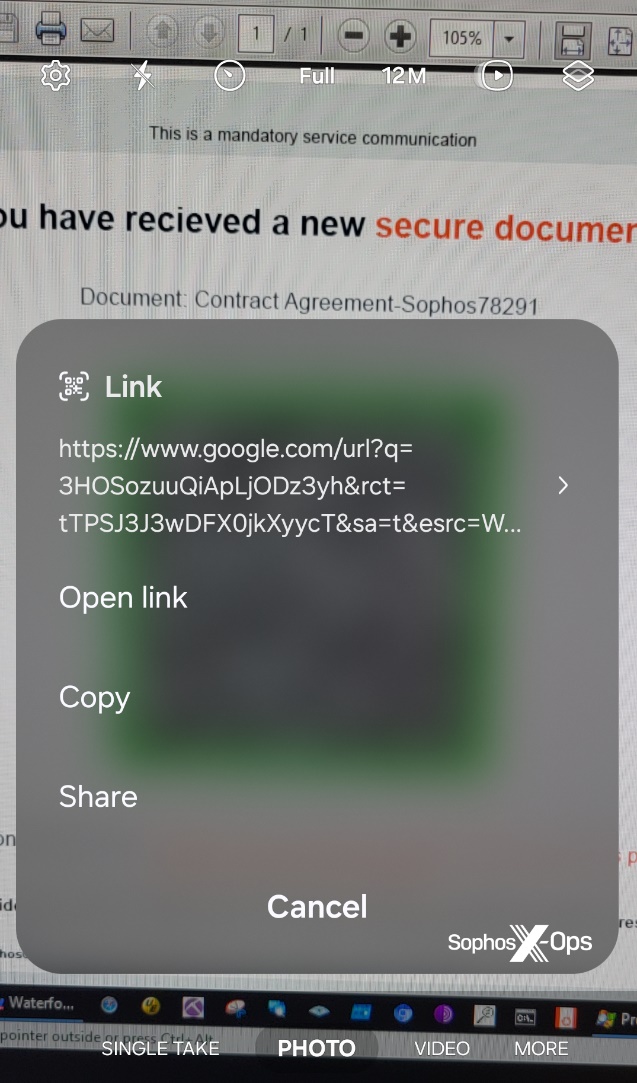

The formatting of the link the QR code points to has also evolved. While many of the URLs appear to point to conventional domains that are being used for malicious purposes, attackers are also leveraging a wide variety of redirection techniques that obfuscate the destination URL.

For instance, one quishing email sent to a different Sophos employee in the past month linked to a cleverly formatted Google link that, when clicked, redirects the visitor to the phishing site. Performing a lookup of the URL in this case would have resulted in the site linked directly from the QR code (google.com) being classified as safe. We’ve also seen links point to shortlink services used by a variety of other legitimate websites.

Any solution that purports to intercept and halt the loading of quishing websites must address the conundrum of following a redirection chain to its eventual destination, then performing a reputation check of that site, along with addressing the added complication of phishers and quishers hiding their sites behind services like CloudFlare.

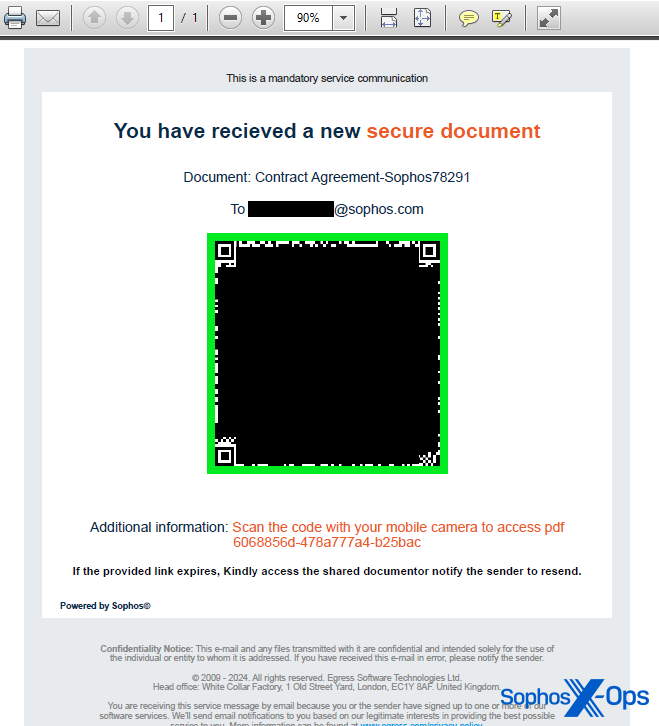

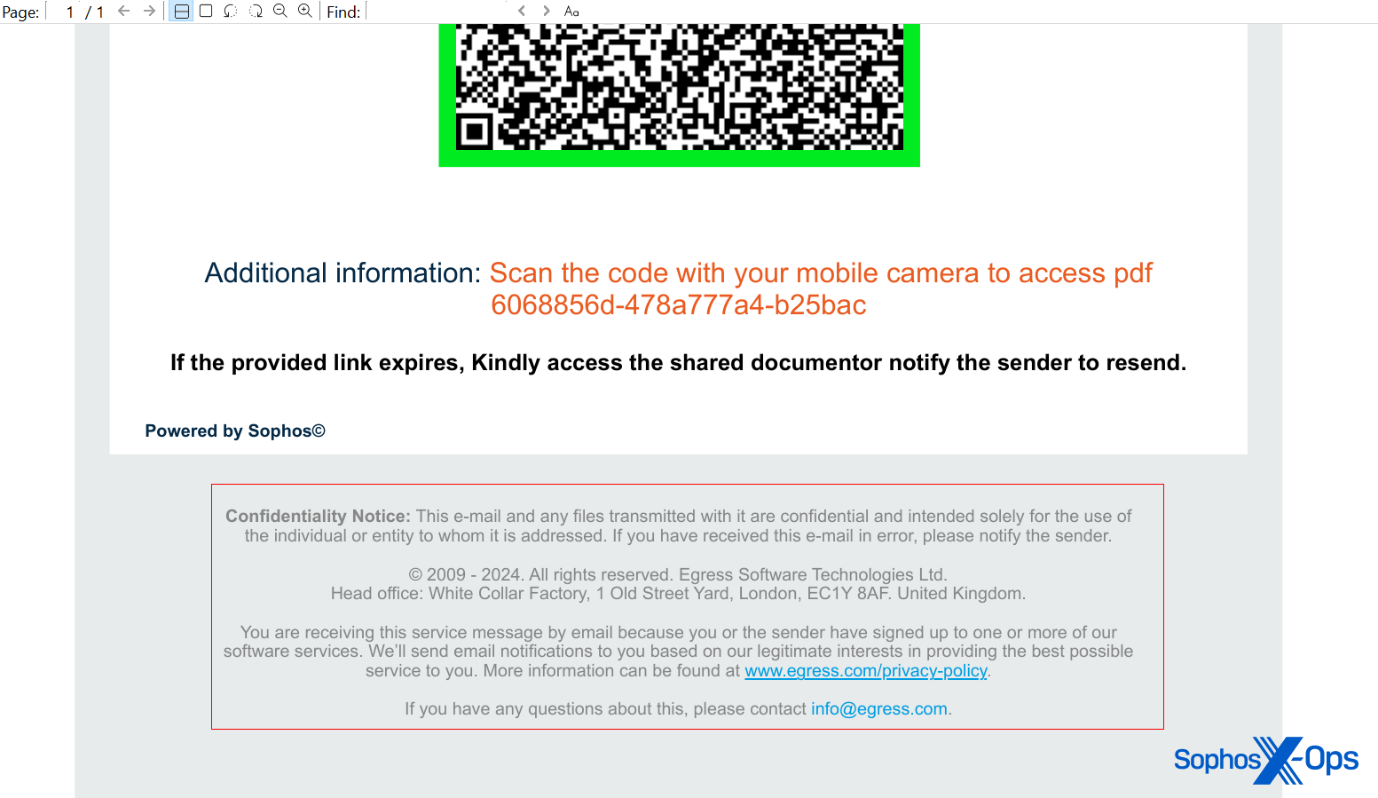

The more recent quishing email sent to a Sophos employee had a PDF attachment with an ironic twist – it appeared to be sent by a company whose primary business is anti-phishing training and services.

The PDF attached to the more recent Sophos-targeted quishing email had footer information that appears to mimic legal notices from a company called Egress, a subsidiary of the anti-phishing training firm KnowBe4. However, the domain the QR code pointed to belongs to a Brazilian consulting firm that has no connection to KnowBe4. It appears that the consultants’ website had been compromised and used for hosting a phishing page.

That message also contained body text that made it appear it was an automated message, though it had some very curious misspellings and errors. As with the previous messages, the body text indicated a filename for the attachment that did not match what was attached to the email.

MITRE ATT&CK Tactics Observed

Recommendation and guidance for IT admins

If you are dealing with a similar QR-code-enabled phishing attack in an enterprise setting, we have some suggestions about how to deal with these types of attacks.

- Subject matter focused on HR, payroll, or benefits: Most of the quishing emails targeting Sophos use employee paperwork as a social engineering ruse. Messages had subject lines that contained phrases like “2024 financial plans,” “benefits open enrollment,” “dividend payout,” “tax notification,” or “contract agreement.” However, none of the messages came from a Sophos email address. Pay particular attention to messages with similar subject matter, and ensure that all legitimate messages pertaining to these subjects come from an email address internal to your organization, rather than relying on third party messaging tools.

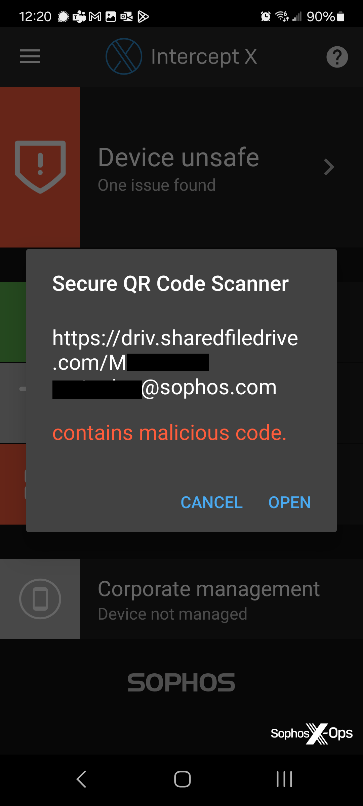

- Mobile Intercept X: Intercept X for Mobile (Android/iOS) includes a Secure QR Code Scanner, available through the hamburger menu in the upper left corner of the app. The Secure QR Code Scanner protects users by checking QR code links against a database of known threats and warns you if Sophos’ URL reputation service knows a website is malicious. However, it has the limitation that it does not follow links through a redirection chain.

- Monitor risky sign-in alerts: Leverage Microsoft’s Entra ID Protection, or similar enterprise-level identity management tooling, to detect and respond to identity-based risks. These features help identify unusual sign-in activity that may indicate phishing or other malicious activities.

- Implementing Conditional Access: Conditional Access in Microsoft Entra ID allows organizations to enforce specific access controls based on conditions such as user location, device status, and risk level, enhancing security by ensuring only authorized users can access resources. Wherever possible, similar defense-in-depth procedures should be considered as a backstop for potentially compromised MFA tokens.

- Enable effective access logging: While we recommend enabling all the logging described here by Microsoft, we especially suggest enabling audit, sign-ins, identity protections, and graph activity logs, all of which played a vital role during this incident.

- Implement advanced email filtering: Sophos has already released phase 1 of Central Email QR phish protection, which detects QR codes that are directly embedded into emails. However, in this incident, the QR code was embedded in a PDF attachment of an email, making it difficult to detect. Phase 2 of Central Email QR code protection will include attachment scanning for QR codes and is planned for release during the first quarter of 2025.

- On-demand clawback: Sophos Central Email customers who use Microsoft365 as their mail provider can use a feature called on-demand clawback to find (and remove) spam or phishing messages from other inboxes within their organization that are similar to messages already identified as malicious.

- Employee vigilance and reporting: Enhancing employee vigilance and prompt reporting are crucial for tackling phishing incidents. We recommend implementing regular training sessions to recognize phishing attempts, and encouraging employees to report any suspicious emails immediately to their incident response team.

- Revoking questionable active user sessions: Have a clear playbook on how and when to revoke user sessions that may show signs of compromise. For O365 apps, this guidance from Microsoft is helpful.

Be good to your humans

Even under the best conditions, and with a well-trained workforce like the employees here at Sophos, various forms of phishing remain a persistent and ever-more-dangerous threat. Fortunately, with the right level of layered protection, it’s now possible to mitigate even something as potentially serious as a successful phishing attack.

But just as important as the technical prevention tips above are the human elements of an attack. Cultivating a culture and work environment where staff are empowered, encouraged, and thanked for reporting suspicious activity, and where infosec staff can rapidly investigate, can make the difference between a mere phishing attempt and a successful breach.

Going deeper

Sophos X-Ops shares indicators of compromise for these and other research publications on the SophosLabs Github.