LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) is a new technique for fine tuning large scale pre-trained

models. Such models are usually trained on general domain data, so as to have

the maximum amount of data. In order to obtain better results in tasks like chatting

or question answering, these models can be further ‘fine-tuned’ or adapted on domain

specific data.

It’s possible to fine-tune a model just by initializing the model with the pre-trained

weights and further training on the domain specific data. With the increasing size of

pre-trained models, a full forward and backward cycle requires a large amount of computing

resources. Fine tuning by simply continuing training also requires a full copy of all

parameters for each task/domain that the model is adapted to.

LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models

proposes a solution for both problems by using a low rank matrix decomposition.

It can reduce the number of trainable weights by 10,000 times and GPU memory requirements

by 3 times.

Method

The problem of fine-tuning a neural network can be expressed by finding a \(\Delta \Theta\)

that minimizes \(L(X, y; \Theta_0 + \Delta\Theta)\) where \(L\) is a loss function, \(X\) and \(y\)

are the data and \(\Theta_0\) the weights from a pre-trained model.

We learn the parameters \(\Delta \Theta\) with dimension \(|\Delta \Theta|\)

equals to \(|\Theta_0|\). When \(|\Theta_0|\) is very large, such as in large scale

pre-trained models, finding \(\Delta \Theta\) becomes computationally challenging.

Also, for each task you need to learn a new \(\Delta \Theta\) parameter set, making

it even more challenging to deploy fine-tuned models if you have more than a

few specific tasks.

LoRA proposes using an approximation \(\Delta \Phi \approx \Delta \Theta\) with \(|\Delta \Phi| << |\Delta \Theta|\).

The observation is that neural nets have many dense layers performing matrix multiplication,

and while they typically have full-rank during pre-training, when adapting to a specific task

the weight updates will have a low “intrinsic dimension”.

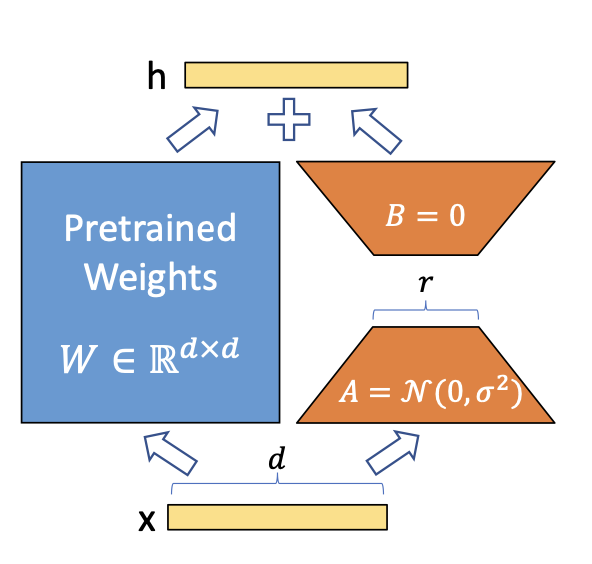

A simple matrix decomposition is applied for each weight matrix update \(\Delta \theta \in \Delta \Theta\).

Considering \(\Delta \theta_i \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times k}\) the update for the \(i\)th weight

in the network, LoRA approximates it with:

\[\Delta \theta_i \approx \Delta \phi_i = BA\]

where \(B \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times r}\), \(A \in \mathbb{R}^{r \times d}\) and the rank \(r << min(d, k)\).

Thus instead of learning \(d \times k\) parameters we now need to learn \((d + k) \times r\) which is easily

a lot smaller given the multiplicative aspect. In practice, \(\Delta \theta_i\) is scaled

by \(\frac{\alpha}{r}\) before being added to \(\theta_i\), which can be interpreted as a

‘learning rate’ for the LoRA update.

LoRA does not increase inference latency, as once fine tuning is done, you can simply

update the weights in \(\Theta\) by adding their respective \(\Delta \theta \approx \Delta \phi\).

It also makes it simpler to deploy multiple task specific models on top of one large model,

as \(|\Delta \Phi|\) is much smaller than \(|\Delta \Theta|\).

Implementing in torch

Now that we have an idea of how LoRA works, let’s implement it using torch for a

minimal problem. Our plan is the following:

- Simulate training data using a simple \(y = X \theta\) model. \(\theta \in \mathbb{R}^{1001, 1000}\).

- Train a full rank linear model to estimate \(\theta\) – this will be our ‘pre-trained’ model.

- Simulate a different distribution by applying a transformation in \(\theta\).

- Train a low rank model using the pre=trained weights.

Let’s start by simulating the training data:

We now define our base model:

model <- nn_linear(d_in, d_out, bias = FALSE)We also define a function for training a model, which we are also reusing later.

The function does the standard traning loop in torch using the Adam optimizer.

The model weights are updated in-place.

train <- function(model, X, y, batch_size = 128, epochs = 100) {

opt <- optim_adam(model$parameters)

for (epoch in 1:epochs) {

for(i in seq_len(n/batch_size)) {

idx <- sample.int(n, size = batch_size)

loss <- nnf_mse_loss(model(X[idx,]), y[idx])

with_no_grad({

opt$zero_grad()

loss$backward()

opt$step()

})

}

if (epoch %% 10 == 0) {

with_no_grad({

loss <- nnf_mse_loss(model(X), y)

})

cat("[", epoch, "] Loss:", loss$item(), "\n")

}

}

}The model is then trained:

train(model, X, y)

#> [ 10 ] Loss: 577.075

#> [ 20 ] Loss: 312.2

#> [ 30 ] Loss: 155.055

#> [ 40 ] Loss: 68.49202

#> [ 50 ] Loss: 25.68243

#> [ 60 ] Loss: 7.620944

#> [ 70 ] Loss: 1.607114

#> [ 80 ] Loss: 0.2077137

#> [ 90 ] Loss: 0.01392935

#> [ 100 ] Loss: 0.0004785107OK, so now we have our pre-trained base model. Let’s suppose that we have data from

a slighly different distribution that we simulate using:

thetas2 <- thetas + 1

X2 <- torch_randn(n, d_in)

y2 <- torch_matmul(X2, thetas2)If we apply out base model to this distribution, we don’t get a good performance:

nnf_mse_loss(model(X2), y2)

#> torch_tensor

#> 992.673

#> [ CPUFloatType{} ][ grad_fn = ] We now fine-tune our initial model. The distribution of the new data is just slighly

different from the initial one. It’s just a rotation of the data points, by adding 1

to all thetas. This means that the weight updates are not expected to be complex, and

we shouldn’t need a full-rank update in order to get good results.

Let’s define a new torch module that implements the LoRA logic:

lora_nn_linear <- nn_module(

initialize = function(linear, r = 16, alpha = 1) {

self$linear <- linear

# parameters from the original linear module are 'freezed', so they are not

# tracked by autograd. They are considered just constants.

purrr::walk(self$linear$parameters, \(x) x$requires_grad_(FALSE))

# the low rank parameters that will be trained

self$A <- nn_parameter(torch_randn(linear$in_features, r))

self$B <- nn_parameter(torch_zeros(r, linear$out_feature))

# the scaling constant

self$scaling <- alpha / r

},

forward = function(x) {

# the modified forward, that just adds the result from the base model

# and ABx.

self$linear(x) + torch_matmul(x, torch_matmul(self$A, self$B)*self$scaling)

}

)We now initialize the LoRA model. We will use \(r = 1\), meaning that A and B will be just

vectors. The base model has 1001×1000 trainable parameters. The LoRA model that we are

are going to fine tune has just (1001 + 1000) which makes it 1/500 of the base model

parameters.

lora <- lora_nn_linear(model, r = 1)Now let’s train the lora model on the new distribution:

train(lora, X2, Y2)

#> [ 10 ] Loss: 798.6073

#> [ 20 ] Loss: 485.8804

#> [ 30 ] Loss: 257.3518

#> [ 40 ] Loss: 118.4895

#> [ 50 ] Loss: 46.34769

#> [ 60 ] Loss: 14.46207

#> [ 70 ] Loss: 3.185689

#> [ 80 ] Loss: 0.4264134

#> [ 90 ] Loss: 0.02732975

#> [ 100 ] Loss: 0.001300132 If we look at \(\Delta \theta\) we will see a matrix full of 1s, the exact transformation

that we applied to the weights:

delta_theta <- torch_matmul(lora$A, lora$B)*lora$scaling

delta_theta[1:5, 1:5]

#> torch_tensor

#> 1.0002 1.0001 1.0001 1.0001 1.0001

#> 1.0011 1.0010 1.0011 1.0011 1.0011

#> 0.9999 0.9999 0.9999 0.9999 0.9999

#> 1.0015 1.0014 1.0014 1.0014 1.0014

#> 1.0008 1.0008 1.0008 1.0008 1.0008

#> [ CPUFloatType{5,5} ][ grad_fn = ] To avoid the additional inference latency of the separate computation of the deltas,

we could modify the original model by adding the estimated deltas to its parameters.

We use the add_ method to modify the weight in-place.

with_no_grad({

model$weight$add_(delta_theta$t())

})Now, applying the base model to data from the new distribution yields good performance,

so we can say the model is adapted for the new task.

nnf_mse_loss(model(X2), y2)

#> torch_tensor

#> 0.00130013

#> [ CPUFloatType{} ]Concluding

Now that we learned how LoRA works for this simple example we can think how it could

work on large pre-trained models.

Turns out that Transformers models are mostly clever organization of these matrix

multiplications, and applying LoRA only to these layers is enough for reducing the

fine tuning cost by a large amount while still getting good performance. You can see

the experiments in the LoRA paper.

Of course, the idea of LoRA is simple enough that it can be applied not only to

linear layers. You can apply it to convolutions, embedding layers and actually any other layer.

Image by Hu et al on the LoRA paper